|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMESArecibo Observatory Signals Aid Search For Extraterrestrial IntelligenceSupercomputing '@Home' Paying Off for Other ResearchBy GEORGE JOHNSON

April 28, 2002

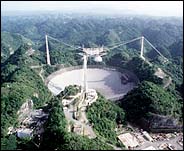

SETI@home, a distributed computing project, analyzes signals received by this radio observatory in Arecibo, P.R. At any time, each volunteer's computer processes a brief segment of a signal from Arecibo. Sometime late this spring, if all goes as planned, SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, will reach a milestone: it will have spent a million years of computer time sifting the electromagnetic noise emanating from the sky for a sign that someone or something is trying to get in touch. SETI has accomplished this feat of computational drudgery in just three ordinary years – by persuading some 3.5 million people to allow their personal computers to be yoked into a loose-knit skein called SETI@home. While no alien messages have been discovered yet, the project's success in using the Internet to assemble an impromptu grass-roots supercomputer is inspiring other researchers to turn to the masses for problems requiring more computation than they could otherwise afford. Volunteers for the Folding@home and Genome@home projects offer up their computers' spare moments to run complex simulations that address problems in computational biology, like how a protein bunches up into the complex shape that determines its role in the machinery of life. Evolution@home is studying how genetic mutations can radiate through a species, and FightAIDS @home is one of many efforts to test possible new drug designs. Other projects (without the obligatory @'s in their names) are searching for prime numbers millions of digits long, cracking cryptographic schemes and trying to predict the weather 50 to 100 years from now. "Even if we were given all the National Science Foundation supercomputing centers combined for a couple of months, that is still fewer resources than we have now, said Dr. Vijay Pande, the Stanford University biologist who directs Folding@home. Last year Dr. Pande's research group set a record by using its volunteer network to simulate 38 microseconds of the folding of a snippet of protein called the beta-hairpin. That doesn't sound like much, but the previous record was one microsecond, and that took several months on a Cray supercomputer. In November, a different kind of milestone was reached when Gimps, for Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search, found the largest known number that has no factors. At more than four million digits, it is about twice the length of "Don Quixote" and took more than two years and tens of thousands of computers to find. (Mersennes, named for the 17th-century French mathematician Marin Mersenne, are numbers with a form that makes them easier to test for primeness.) All of this marathon computing has become possible because of the vast amount of excess computing power in the world. When you lean back from your computer for a moment, the Pentium inside continues churning at a rate of hundreds of millions of times a second. To computer scientists, that is as wasteful as leaving your car idling while you run into the store. Hence the appeals to donate these "spare processing cycles" to the scientific charity of your choice. SETI@home, though not the first, has set the example. You begin by downloading a free piece of software that runs unobtrusively in the background, analyzing the outpouring of data – in this case signals received by the Arecibo Radio Observatory in Puerto Rico. Amid the din of radiating stars, an orderly train of pulses may conceivably be a message. One by one, SETI's servers automatically dispatch 107-second snippets of the cacophony to your computer. It begins crunching away, looking for promising patterns, and 10 to 50 hours later it automatically sends back the results and asks for more. You have become a node in an amorphous supercomputer that, by some measures, matches the world's most powerful. Among computers inside a single building, the honor now goes to one recently installed at the Japanese government's Earth Simulator Research and Development Center in Yokohama, for climate prediction and other problems. Occupying a space the size of four basketball courts, it is rated at 35.6 teraflops, meaning that it can do 35.6 trillion calculations (gloating point operations, or flops) a second. SETI's network – with half a million or more personal computers at any moment – recently reached the very same speed. It sprawls across the seven continents, including Antarctica, where 194 computers have contributed almost 300 "C.P.U. years." (A C.P.U., for central processing unit, is simply a computer.) "People have been locked into this supercomputing mentality," Dr. David P. Anderson, the SETI@home project director, said. "They want to have some gigantic thing in a box somewhere. I think that approach will ultimately go the way of the dinosaurs." Distributed computing has another advantage: unlike an ordinary computer, the grass-roots networks automatically upgrade themselves as people succumb to the desire for faster machines. "We benefit from Moore's law," Dr. Anderson said, referring to the dictum that computing power doubles about every 18 months. "Every year we're twice as fast, and on top of that, more users are joining all the time." For many problems, an in-house supercomputer still has an enormous advantage: packed closely together and connected with high-speed cable, its thousands of microprocessors can rapidly exchange information, updating each other on the fly. For many problems, this kind of constant communication is crucial. With the @home computers, the nodes are scattered across the planet, many communicating through low-speed dial-up modems, and can be incommunicado for days. But sometimes you can get by on sheer brute-force computing power. The challenge is to find a way to break up a problem into chunks that can be processed independently and combined later on. For SETI@home the procedure is fairly straightforward: at any one time each volunteer is working on a brief segment of a signal from Arecibo. Far more challenging to subdivide is a problem like protein folding. When one of these long molecules rolls off the cellular assembly line, it consists of a chain of dozens or hundreds of chemical units called amino acids. Then it begins to crumple, its segments jockeying for position in a three-dimensional tug of war so complex that simulating just one microsecond can take months of supercomputing time. Using sophisticated statistical techniques, the Folding@home team broke up a very simple folding problem into thousands of pieces that could be farmed out over the Internet for analysis. The results were then reassembled into a simulation of a small amino-acid chain doubling up into the shape of a hairpin. "A lot of people never believed the kind of calculations we do could be chopped up this way," Dr. Pande said. Since then the team has been working to simulate longer folding times. The ultimate goal – nowhere in sight – is to start with the description of an amino acid sequence and predict the final shape of the protein. In a closely related effort, Genome @Home is analyzing some of the copious data gleaned from the Human Genome Project. This is all part of the larger, and computationally intense, problem of drug design – searching through a vast "space" of possible protein shapes for one that will interrupt the metabolism of a virus or other biological invader. So many laboratories are asking for spare cycles that computer users must pick and choose lest they bog down their processors combating H.I.V., anthrax, smallpox, Ebola, multiple sclerosis, tuberous sclerosis complex and various cancers and neuromuscular diseases. (A list is available at www.aspenleaf.com /distributed.) Mathematicians and cryptographers were the first to see the possibilities of Internet computing. In 1996 Gimps began searching for prime numbers, which because of their indivisible nature are sometimes called the atoms of the number system. Besides their interest to number theorists, primes are used to encrypt sensitive information on the Internet. Discovering the four-million-digit prime has inspired the group to go after a $100,000 prize offered by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit organization involved in privacy issues, for finding one with 10 million digits. (Bagging one a billion digits long would earn $250,000.) Another of the earliest projects, called distributed.net, also cracks cryptographic codes and is trying to find something called an optimal golomb ruler, a mathematical artifact important to coding and communications theory. (No two marks on the ruler can be separated by the same distance, a constraint that makes finding longer and longer ones exponentially more difficult.) With more of science becoming dependent on highly complex calculation, the demand for surplus cycles seems endless. Climateprediction.com is recruiting people to take on one of the hardest problems of all: predicting the effects of climatic change, including global warming. By running multiple simulations of the atmosphere and oceans, each tweaked a little differently, the researchers hope to test various possibilities for the years 2050 and 2100. Dr. Anderson of SETI@home says he is not worried by all the competition. "There is plenty of computing power," he said. "SETI@home has approximately 1 percent of the computers on the Internet. There is still that other 99." He and his colleagues have been working on software that will make it easier for other scientific efforts to take advantage of the Internet's untapped resources. One vital ingredient is arresting animation – gyrating proteins, mountain ranges of SETI data being analyzed. These sophisticated cartoons (known in the trade as cool graphics) sap processor power that could go toward analyzing the data. But they keep computer owners motivated by giving them a sense that something interesting is going on. That raises a problem that does not occur with an insentient beast like the Japanese supercomputer – persuading it that your problem is worth fooling with. With the Internet, Dr. Anderson said, "you can divvy up your computing power according to your desires. Do you want 70 percent to go to simulating global climate and 30 percent to go to searching for ET's? It is the task of each project to convince the world that what it is doing is important, and get a proportional amount of computing power."

|

PHOTO: Dr. Seth Shostak

PHOTO: Dr. Seth Shostak