|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. One Island, Three Views… Issues Need To Be Addressed… Island Struggles To Find Its Place

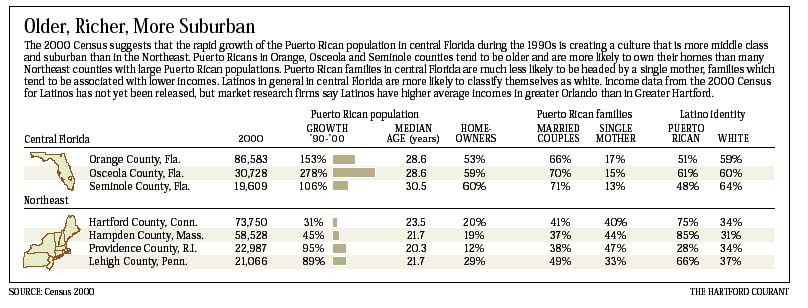

July 21, 2002 On July 25, 1952, the government of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico was sworn in, and the Puerto Rican flag was adopted. The question facing a changing island today: Does its relationship with the United States still work? Some say no.

Carlos I. Pesquera | President, New Progressive Party Pro-statehood The migration of Puerto Ricans to this state has made many Floridians aware of Puerto Rico's status conundrum: whether it is, or should become, part of the United States or an independent country. To be sure, Puerto Rico fits with none of the scenarios. It is not foreign, because Congress reigns supreme over its territory and inhabitants. It is not part of the American homeland, because Congress has not incorporated to its national territory an Enchanted Island of the Caribbean over which the American flag has flown for more than a century.

Under such status, all federal laws apply to Puerto Rico, even when its inhabitants have no votes in Congress. Puerto Ricans living on the island are sent into battle by a commander in chief for whom they do not vote. And Puerto Ricans are processed in courts and by judges in whose creation or appointment they do not have a say. Puerto Rico cannot even choose its ultimate status. Only Congress can decide that. Hence, we call the political status of the island, simply, colonial. Puerto Ricans, on the other hand, are American citizens, proud to share their nation with the full array of ethnic groups united under Old Glory. In 1917, Congress made people born on the island members of the American body politic. Since then, Puerto Ricans have been proud, productive and brave Americans. As such, we have contributed to the defense, development and well-being of our nation. Not all Puerto Ricans, however, are allowed to enjoy their citizenship to its fullest. Those who live in Florida and the other states are equal under the law with all their fellow citizens. However, it is a sad fact that Puerto Ricans living on the island cannot participate fully in our American society, with complete rights and duties. Even more sadly, for decades Congress has ignored our petition to be formally consulted regarding our preferences among congressionally defined options for our future. In such a contest, statehood would enjoy a handsome majority. Colonialism and congressional neglect have led some Puerto Ricans, such as those who defend the other status formulas, to reject our natural aspiration to enjoy the fullness of our rights and duties by becoming a state. Some of these people would, just as any confused or abandoned kid, reject the possibility of becoming an integral member of the family. America must be great and united in celebration of diversity. That is our nature and our strength. It is my commitment that the American flags that now fly over Puerto Rico will never be lowered to cede this American territory to any other government, either existing or to be created. To be a Puerto Rican, in Orlando or in San Juan, is nothing but to be a proud American of a particular ethnic extraction. The sooner Congress initiates the territory of Puerto Rico on the road to statehood, the sooner a better future will be coming to us all.

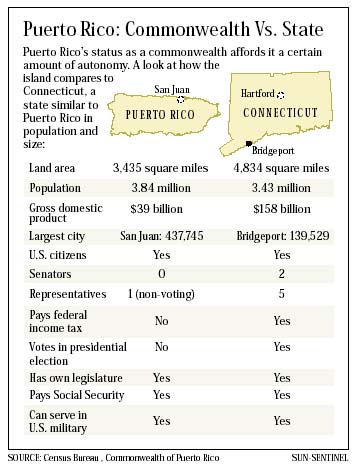

By Sila M. Calderón | Governor of Puerto Rico Pro-commonwealth ---------- Puerto Rico: commonwealth vs. state ---------- For half a century, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico has continuously opened new doors of freedom, self-government, prosperity and increasing self-confidence for Puerto Ricans. It has helped to liberate the creative capacities of our people, providing a solid social, political and economic platform from which to leap forward collectively into the future. Commonwealth has been a vehicle for allowing our distinct national identity and cultural personality to flourish, while retaining the U.S. citizenship we treasure. It has provided the necessary space for a people with a different background, history and language to maintain their allegiance to the United States and to the ideals of freedom and democracy that it represents, while remaining autonomous in order to decide our own internal affairs. It represents a middle course between the extremes of total assimilation through statehood and separation through independence. Commonwealth has been a powerful tool for economic development, as well, granting us the fiscal autonomy that allows us to collect our own revenues and set our own fiscal policies, fully devoting the taxes collected from our people to addressing our own special needs, which are different from the rest of the nation. The benefits of that fiscal autonomy far outweigh the fact that we do not vote for president and have no voting representation in Congress. It is based on that fiscal autonomy, which entails the island's exemption from federal taxation, that Puerto Rico's tax-incentive laws have allowed us to attract industrial investment. Since commonwealth was established, the island's economy has developed dramatically, raising per-capita income from $374 dollars per year (in present dollars) in 1952 to $9,870 dollars per year now. Economically, commonwealth has been good for both Puerto Rico and the United States. It has allowed a small island with only 3.9 million people to become the 10th largest purchaser of U.S. goods in the world. Socially and culturally, commonwealth has allowed for significant results. Life expectancy was raised to the levels of the advanced nations. Thousands of families were able to achieve their dream of home ownership. Educational opportunities have been so broadened that many U.S. firms and city governments recruit our graduates. Commonwealth has also opened new opportunities for cultural expression. Many of our artists, singers, musicians, and actors have become world known. I remain firmly convinced that the way for Puerto Rico to best respond to the need for promoting further economic development and social justice is through commonwealth. While reconciliation must be at the very heart of any successful approach to the Puerto Rican status issue, commonwealth must strengthen and evolve to continue to play its role as the common-ground solution favored by the majority of Puerto Ricans. Puerto Rico needs to be economically as strong and self sufficient as it can be. This requires freeing it from some federal policies that are good for the 50 states, but that have an undesirable impact upon the island. Strengthening commonwealth, solidifying its legal bases, promoting it further as a middle road to freedom, is, moreover, a two-way street. I proposed establishing a means for achieving consensus among the three factions as to the process to be used with Congress for a revision of our commonwealth status. That is our responsibility. But the United States also has a responsibility: to respond, to be sensitive to the continuing needs of our people, to establish a meaningful dialogue through which the needed adjustments can be devised.

Colonialism Denies Our Rights By Manuel Rodríguez Orellana | Secretary of North American relations for the Puerto Rican Independence Party Pro-independence When I was a child, my grandmother taught me a proverb commonly used in Puerto Rico: Cada cual en su casa, y Dios en la de todos. Roughly translated, it means, "each person should mind her own house, while God tends to all." As I grew up, I found its great wisdom helped me to get along with relatives, friends, and neighbors. Today, it also provides the best common sense reason for Puerto Rico's national independence. Americans should particularly understand how history, geography, language and race blend peoples from various origins and cultures into a distinct national existence. As a result of a unique 400-year-old historical experience, Puerto Rico was a nation already when the United States invaded and took over in 1898. The Taíno Indians, dwindled in numbers after their brutal enslavement by the Spanish conquerors, mixed with the Spanish criollos and the African slaves. Later, immigrants from other places in South America and Europe also blended with immigrants from North America and the Middle East into a distinct Spanish-speaking, Latin American nation of the Caribbean. Recently , one of my doctors, a native of Italy married to an American woman, showed me a school composition by his daughter, born in Humacao, Puerto Rico, only 12 years ago. She beautifully expressed her "love" for Puerto Rico and identified herself as Puerto Rican. Thus our nationality keeps on course even after ridiculous U.S. attempts at "Americanization." The natural political condition for people of diverse nationalities is juridical sovereignty. Puerto Rico's unnatural condition as a nation -- governed by laws it does not make, by rulers it does not elect, and butchered in wars it does not declare -- is the result of the U.S. invasion more than a century ago. Puerto Rico's condition is called colonialism, and its remedy is decolonization. In a world populated by nearly 200 independent nations, Puerto Rico's colonial status, whether called a territory, a commonwealth or even a federated state, would still be an historical anachronism. Moreover, the domination of human beings by others raises moral questions, such as those settled in the United States with the abolition of slavery. Colonialism constitutes a denial of fundamental human rights. Most arguments advanced against Puerto Rico's inalienable right to independence are remnants of the Cold War. In the past decade, smaller and poorer nations have fared economically much better than Puerto Rico, while Puerto Rico has not surpassed anyone's economic development. But the U.S. war industry has acted against democracy to persecute and discriminate against those in Puerto Rico who, like the American patriots who fought against England in 1776, opposed colonialism. Without the tools of national sovereignty in today's interdependent, global markets, Puerto Rico can only look toward a future of economic isolation, stagnation and greater dependency on federal transfer payments under an outdated military policy that only views the island as a strategic outpost.

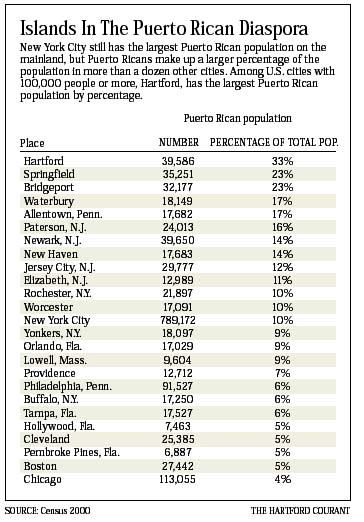

Issues Need To Be Addressed July 21, 2002 Puerto Rico's Commonwealth status turns 50 this week and appears to have reached a midlife crisis. Congress created the Commonwealth pact in 1952 as a way to decolonize Puerto Rico. The status gave the island a constitution and enhanced self-rule. It also helped transform Puerto Rico from a backward rural society to one with a modern industrial base. As such, Puerto Rico became a U.S. showcase for democracy and economic progress in Latin America. But the showcase has lost its luster. Puerto Rico's economy is stagnant, and Congress is phasing out corporate tax incentives that have bolstered Puerto Rico's economy since World War II. In the meantime, the island's jobless rate remains high, at 11 percent, and this has prompted many middle-class and professional Puerto Ricans to migrate. Florida is one place where they have settled. South Florida's Puerto Rican community nearly doubled in the past decade, to about 160,000, making it the region's second largest Hispanic group. The link between the United States and Puerto Rico remains strong. As U.S. citizens, since 1917, Puerto Ricans travel freely between the island and the mainland United States. In Puerto Rico, residents enjoy civil liberties guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, and these are precious. But Puerto Rico lacks the political freedom to determine its future. Congress, with some nudging from the White House, needs to address this democratic problem. Certainly, Puerto Ricans need to make up their mind about what status they prefer, but only Congress can define the choices. Over the past 100 years, it hasn't done so. As things now stand, Congress has ultimate say over Puerto Rico, but Puerto Rico has no votes in that body. Puerto Rican voters have consistently supported commonwealth in various non-binding plebiscites. In these votes, Puerto Ricans have asked for greater autonomy under commonwealth, and the requests have been ignored by Washington. Today, Puerto Rico's voters are about equally divided between commonwealth and statehood, with a small minority favoring independence. The choices raise difficult issues that need to be addressed. These include economic issues. Puerto Rico, which has 3.9 million residents, has about half the per capita income of Mississippi, the poorest state. As a state, Puerto Rico would qualify for about double the federal aid and transfer payments that it now receives, or about $11 billion. Puerto Rico's residents don't pay federal income taxes. Yet Puerto Rico is the 9th largest market for U.S. goods in the world, surpassing even China. More than 300,000 mainland U.S. jobs depend on Puerto Rico. The most difficult roadblock to statehood, however, is cultural rather than economic. Puerto Rico would be the United States' first Spanish-speaking state with a distinct culture. Puerto Rico needs a clear path to self-determination, as a commonwealth with more autonomy, an independent nation, or a state with represenatation in Congress. The issues raised by all three alternatives will be difficult to resolve, but Congress must address them now, not in another 50 years.

Island Struggles To Find Its Place By Iván Román July 21, 2002

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico -- The ruling Popular Democratic Party, which helped create Puerto Rico 's commonwealth status , likes to tout the island's ties to a strong U.S. economy. The relationship, they say, has made the island a richer, industrialized society and allowed Puerto Ricans -- United States citizens since 1917 -- to preserve their culture and language. However, as the commonwealth enters its 50th year Thursday, it is showing clear signs that the status forged as an alternative to statehood and independence in 1952 is outgrowing itself. Even some defenders say the commonwealth needs to evolve into what its founders envisioned -- a place with more sovereignty so it can trade directly with foreign countries, or enforce its constitutional ban on the death penalty that now conflicts with federal law. Supporters and critics alike are looking at ways for Puerto Rico, established essentially as a military colony and primed for decades as an economic haven for U.S. interests and corporations, to survive in a global economy while being less dependent on American capital. Recent protests over the U.S. Navy's use of Vieques for bombing practice taught political friends and foes that it was OK to unite and challenge Washington and the U.S. military, something that would have been unthinkable 10 years ago. "The events in the last three years have changed radically the perception of commonwealth status on both sides, in San Juan and in Washington," political analyst Juan Manuel Garcia Passalacqua said. "It's posed the issue exclusively on the paradigm of loyalty. The issue is, can the Puerto Ricans be loyal to the U.S.?" Outgrowing the past The conflicting answers are proving to be the Achilles heel of those pushing for Puerto Rico to become the 51st state. Commonwealth advocates talk of loyalty but at arm's length -- a "partnership" with the U.S. that has served them well while allowing room for Puerto Rico to be a distinct cultural "nation." Hogwash, say statehood and independence advocates. They call Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory subject to the jurisdiction of Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court, a colony despite its self-government and fiscal autonomy. If Puerto Rico were a state and had voting representatives in Congress, its share of money for roads, food stamps and a host of other programs based on population would be much larger. As it is, the island has less than half the $18,000 per capita income of the poorest state, Mississippi. But it has the highest standard of living in Latin America and the Caribbean. Puerto Ricans on the island don't pay federal income taxes, don't have a vote in Congress and aren't allowed to vote for president. But they are liable for the draft, and tens of thousands of islanders have died since World War I while fighting with the U.S. armed forces. Most of the island's $13 billion in annual federal aid is in entitlement programs such as Social Security that Puerto Ricans pay taxes to support. If Puerto Rico were a state and had voting representatives in Congress, then its share of money for roads, food stamps and a host of other federal programs based on population would be much larger. On the plus side, under the commonwealth, it has achieved the highest standard of living in Latin America and the Caribbean. "Our people were steeped in abject poverty, and we stood together to do justice for poor children, for people forced to squat on large agricultural estates, to break those large interests that were destroying our people," Calderon said as she announced a yearlong celebration of the commonwealth. "You'd have to be deaf and blind to look around you and not see the progress we've had here." History lesson aside, it's today's money problems that are injecting life into the political-status debate. Since federal tax breaks disappeared and factories began moving to places such as the Dominican Republic and Singapore, Puerto Rico has struggled to compete in the global marketplace. Local government officials are lobbying to replace the tax exemption that guaranteed U.S. corporations fat profits. The phasing out of the tax break since 1996 is blamed for the loss of tens of thousands of jobs. But Congress seems to have little interest in approving even modest tax breaks for the island. And some economists think Puerto Rico must now create its own economic capital and diversify into more service-driven enterprises. This would mean less dependence on U.S.-backed manufacturing, which helped change the island from a place where wooden shacks lined the countryside to one where virtually everyone has a cell phone. "We're at a ... unique moment," said constitutional lawyer Noel Colon Martinez. "At 50 years old, those who defend the commonwealth find the relationship unsatisfactory when the program of political development has not happened. For the first time, they see unfavorable politics tied to unfavorable economics." Commonwealth now a hindrance? Some islanders are resting their economic hopes on a major south-coast port -- designed to be one of the hubs in a worldwide-shipping distribution system. But to make it work, commonwealth officials concede Puerto Rico would have to be exempt from controversial shipping laws that mandate using more expensive U.S.-built ships and merchant-marine personnel. Since an exemption from Congress is unlikely, this could happen only by changing political status. And the U.S. has resisted previous attempts by Puerto Rico to push the envelope and join international or regional trade organizations for fear that negotiations might conflict with trade policies. "We're at a very unique moment," constitutional lawyer Noel Colon Martinez. "At 50 years old, those who defend the commonwealth find the relationship unsatisfactory when the program of political development has not happened. For the first time, they see unfavorable politics tied to unfavorable economics." For Sonia Morales, 38, and thousands like her, the problem has been apparent for decades. Her father Mariano Morales, an academic librarian and historian, was punished for his pro-independence beliefs. Unable to find a decent job, he moved his family to the mainland. Sonia Morales, a pianist, composer and arranger, has a master's degree in music from the University of Indiana but hasn't been able to find a good full-time job in her field since she returned to Puerto Rico eight years ago. She supports an independent Puerto Rico but fears it may be too late. "The power is in the dollars, and the Americans have the power," said Morales, currently writing an opera about the slave-trade experience in Puerto Rico. "I don't believe in statehood, but I believe in my children. For them, always the best. And if I have to move to the U.S., I will do it." Political muscle and plane rides The right to move back and forth between the island and the mainland is as Puerto Rican as rice and beans, analysts say, and must be part of any change in status that people would support. U.S. citizenship granted in 1917, just in time for islanders to fight in World War I, opened the door to decades of mass migration as people fleeing poverty in the countryside flocked to Puerto Rico's cities and then to the mainland's northeast region. Now the constant movement of this "commuter nation," as one sociologist calls it, has become a factor in Puerto Rico's hardball politics, with 3.8 million island residents and 2.8 million on the mainland. The Puerto Rican government is spending millions this year to register voters on the mainland in hopes that they, together with highly paid lobbyists, can add to the island's political muscle. Statehooders, although shunning this practice, used some stateside Hispanic organizations to push their agenda in Congress. Puerto Ricans in South Florida span the spectrum of opinion on the island's political status , but there are no studies to gauge local support for the commonwealth, statehood or independence. Raul Duany, chairman of the Puerto Rican Professional Association of South Florida, said debate over the island's status is not as visible an issue among South Florida's Puerto Ricans as the debate over the trade embargo against Cuba, for example, is among Cubans. "It's not, in my mind at least, something that either unites or divides the local community here," Duany said. "I don't think in South Florida you'll find strong sentiment. The status of Puerto Rico has a lot of gray areas, a lot of unknowns." Frances Negron-Muntaner, a Puerto Rican scholar, filmmaker and writer, said many of South Florida's Puerto Ricans are more interested in upward mobility than in politics. They are not as wrapped up in the status debate as Puerto Ricans living on the island. "Puerto Ricans raised in Puerto Rico feel a position on the status is such an important part of who they are, who they relate to, who they trust and, I would even say, the type of person you think you are and the type of person other people think you are," she said. Despite the NPP's costly efforts, statehood failed to win a majority of votes in two referendums on status in 1993 and 1998. Commonwealth supporters edged them out both times, and also defeated statehood in an earlier plebiscite in 1967. In a May 2002 newspaper poll, 60 percent of respondents said Puerto Rico was their "nation," while 20 percent said the United States. Seventeen percent said both. In Washington, statehooders didn't fare much better. In 1998, the House approved by one vote a binding plebiscite on the issue, but the bill died in the Senate. Now, commonwealth advocates are taking a different tack. Calderon is expected to name a commission that she hopes will reach consensus on how to solve the status issue. The options would be a binding plebiscite, a constitutional assembly or some other mechanism -- in hopes of returning to Congress with a united plan of action. The commission's original acronym and nickname meant bogeyman in Spanish and, for some, the name was more than symbolic. Leaving the issue to a committee is a sure way of killing any hopes of progress, critics say. As if to prove them right, pro-statehood politician Leo Diaz last week called it a "committee of lies" intended to court voters without settling anything. The refusal of pro-statehood leaders to participate in the panel would be an "irresponsibility" that would deprive their supporters of a voice in a historic process, pro-commonwealth Secretary of State Ferdinand Mercado retorted. "Calderon knows the push for more sovereignty within the commonwealth won't go anywhere so she is paying lip service to the demand for changes," said Jose Garriga Pico, a political-science professor at the University of Puerto Rico. "So she can have the best of both worlds, pretending to do much as she does nothing." Jorge Rodriguez, who comes from a long line of statehooders, tried to force the issue when he and 11 others sued in federal court in 1999 for the right to vote for president. They alleged discrimination since Puerto Ricans on the mainland or in any foreign country can vote for president, while those on the island can not. After an initial victory, they lost on appeal, but not before spurring pro-statehood Gov. Pedro Rossello to set up presidential balloting, drawing nationwide attention to the issue before the courts finally stopped him. Rodriguez is convinced the commonwealth options will eventually disappear and people will be forced to make a hard choice. "If we are the same on the battlefield, then we have to be the same when it comes to enjoying the fruits of democracy," said Rodriguez of Puerto Ricans pro Permanent Union. "When there is a vote to choose between sovereignty within the U.S. or without the U.S., the people will choose to be within. Our people will not go backwards." Culture as a weapon Maybe not. Still, many say a huge chunk of the population has been stuck in neutral for some time. The shrill political debate is often riddled with confusion and fear -- fear of losing Social Security, food stamps or U.S. citizenship, of having to speak English in government offices or to be educated in English, of ceasing to be who you are. "Statehooders strike fear with the economy, and the commonwealth people drum up the fear about losing our culture," said Ricardo Alegria, a Puerto Rican historian and anthropologist and the Institute for Puerto Rican Culture's first director in 1954. "All of them lie in one way or another. What's needed here is for people to speak clearly so we can all go from there." As recent campaigns to highlight the island's cultural achievements succeed, some wonder if culture is ahead of politics in charting the path to the island's future. Sixty percent of islanders watch U.S. programs on cable television, and 14 percent primarily speak English at home. But most root for Puerto Rican boxers, basketball teams and Miss Universe contestants against their U.S. counterparts. Middle-class professionals send their kids to private schools, prepping them for stateside universities but continue to speak mostly Spanish at home. Like in the U.S., young people pack malls to snatch up expensive jeans, but then sing along with local rock bands calling for independence, simpler living and free thinking. Many Puerto Ricans feel emotionally closer to New York and Orlando, where they constantly go on vacation, than to other Latin American cities or the nearby island of St. Croix, packed with Puerto Ricans since the 1940s. Plagued by contradictions, Garriga Pico said, people may be proud to be Puerto Rican, but messing with grandma's Social Security check is off limits. "It's ethnic pride and not a nationalist feeling, because if it was nationalist feeling, we'd take up arms in the streets like the Palestinians," added Garriga Pico, who favors independence. "And Vieques is not an anti-American issue. For most people, it's a not-in-my-backyard issue." The Vieques factor Many activists and historians strongly disagree, saying that the unprecedented political, civic, religious and labor coalition that energized some 80,000 people for a march against the Navy's presence in Vieques was not a fluke. The Vieques controversy, sparked when an errant bomb killed a security guard in April 1999, uncovered facts about training and environmental issues that made many realize the Navy's activities there for 60 years were bad for Puerto Rico, analysts say. So when prospects were raised of pulling the Navy out of Puerto Rico or removing the Army's Southern Command from San Juan, few politicians, except for statehooders, spoke up. Some activists hope this first major challenge to the military establishment will convince Washington that with the Cold War now history, it's time to let go. "Anybody with any sense would say 60 years of bombing is enough. Leave them alone," said independence supporter Wilfredo Warrington, as he maintained a vigil for jailed protesters outside the federal courthouse in Guaynabo. "Instead, people in Vieques are accused of being anti-American." Warrington, 54, is quick to point out that like many other islanders, he served in the military -- two years in Vietnam -- and he thinks Puerto Ricans have paid their dues. "I went to Vietnam and could have lost my life," he said. "What is that worth? And what about those who came home in a box?" He thinks the island eventually will be independent even if it takes many, many years. Puerto Rico is unique and wouldn't fit in as a state, he says. "Those people over there, none of them speak English," Warrington said, pointing to dozens of people putting up a U.S. flag to counter his pro-independence camp. "That's why statehood will never come."

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

One Island, Three Views

One Island, Three Views Statehood Would Mean A Better Future

Statehood Would Mean A Better Future Hence, Puerto Rico lives in a limbo technically labeled an "unincorporated territory" -- or worse, a "possession," a terminology reminiscent of the "separate-but-equal" mentality of the Supreme Court at the turn of the 20th century.

Hence, Puerto Rico lives in a limbo technically labeled an "unincorporated territory" -- or worse, a "possession," a terminology reminiscent of the "separate-but-equal" mentality of the Supreme Court at the turn of the 20th century.

The Current Status Empowers The Island And The People

The Current Status Empowers The Island And The People