|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. 'It Was The Night The Happiness Died'…Remembering Roberto Clemente…His Legacy

'It Was The Night The Happiness Died' JERRY IZENBERG December 30, 2002

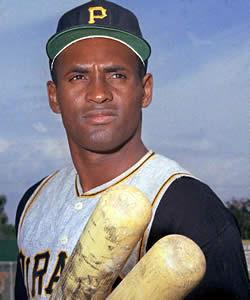

AP File Photo ---------- On New Year's Eve 1972, baseball great Roberto Clemente died when the plane he had chartered to bring supplies to Nicaraguan earthquake victims crashed off the coast of Puerto Rico. Star-Ledger columnist Jerry Izenberg visited the crash scene 30 years ago and returned last week. A web of weather-beaten cracks disfigures the empty building. The mural on the street side has begun to fade in the teeth of three decades of island sun. Nobody even remembers who painted it. But the face of Roberto Clemente still gazes out at Highway 3. This side of the Sanchez Osorio public housing project is empty now, a hollow ghost town waiting for a wrecking ball. But nobody knows what to do with "The Wall." Everyone wants to protect it. The Wall is part mystery, part icon and part of the eternal autograph Roberto Clemente left across the face of the island he loved so much. Not too far away is San Juan, home of Hiram Bithorn Stadium, where Clemente played and managed in winter-league ball. There are ghosts in this ballpark. They roam the outfield on soft Puerto Rican nights and dance lightly on the basepaths in the reflected haze of the overhead lights. "Even today, when I sit in this dugout, I see him as he will always be for me. He is everywhere in this stadium," says Nick Acosta, medical trainer for the Santurce Crabbers and Clemente's longtime friend. "I sit here and shake my head, when I see a kid try to make a play and I say Roberto would have made it. I see another one throw from the outfield and I say Roberto would have nailed the runner by 10 feet. He will always be my measuring stick - as a player and as a person. "He was our hero. He never forgot what it was to be poor and to be one of us. He would see a shoeshine kid and he'd ask him if he'd eaten, and the kid would say no and then Roberto would put his arm around him and say, 'Please come. You must eat with me or I cannot eat.'" Rudy Hernandez sits at the other end of the dugout. He was a pitcher in the American League for a short time, after becoming the first Dominican player to play organized ball in the United States. But he has lived in Puerto Rico for so long, he has become a native by osmosis. He played with and against Clemente in this same ballpark. He is a baseball man who cannot stay away from the ballpark. He still works at it as a scout, a coach, a teacher and a friend to young prospects on the way up and veterans on the way down. "I was born in the Dominican," Hernandez says, "but I've lived on this island for 45 years. I have never seen a time of sadness here like the one that began on the New Year's Eve when we lost Roberto." The DC-7 flying relief supplies to the earthquake victims of Nicaragua under Clemente's supervision never had a chance. It exploded shortly after takeoff from Luis Munoz Marin International Airport in San Juan and plunged to a watery grave just off the coast in less than two minutes. In that instant. New Year's Eve died in Puerto Rico. "The streets were empty, the radios silent, except for news about Roberto," Hernandez says. "Traffic? Except for the road near Punta Maldonado, forget it. All of us cried. All of us who knew him and even those who didn't wept that week. "It was almost 10 or 11 (o'clock) when we got the news. We were having a party to count down the New Year in my restaurant and a friend called and said to turn on the radio. He said Roberto's plane had crashed. And then, because my place was on the beach, we saw those giant searchlights and the light from the flares criss-crossing on the waves and we heard the sound of helicopters," Hernandez says. "Manny Sanguillen, the Pirates catcher, and (Clemente) were very close. Manny was in my joint that night. When he heard the news he and a couple of guys jumped in their car and raced out there. They got a small boat and Manny started diving in the water to see if he could find something. "There are sharks out there, man. I mean real, man-eating sharks and he didn't care. It was craziness. Craziness everywhere. It was ... it was ..." And as Hernandez groped for the words, Nick Acosta moved down the bench and supplied them: "It was the night the happiness died." "There has never been a time when the people were so sad," says Juan Pizarro, a longtime former major-league pitcher and now a coach for Santurce. "It went on for weeks." Roberto Clemente had been the focal point of tens of thousands of hopes and dreams from Aguadilla to Ponce, from Fajardo to Salinas. Wishes and events merge and blur in the retelling of so many. You speak with them and they say: "Oh, it was here that Roberto had his last meal. I have the napkin." Or "Yes, I, myself, saw him at the airport. He looked like a man that knew what was about to happen." The real story begins with the late Luis Vigoreaux. He was the island's leading television personality. When he heard of the Nicaraguan earthquake on Dec. 23 that year, he wanted to help. Only one voice on the island had more power and appeal. He turned to Roberto Clemente, who was receiving an award at the San Juan Hilton Hotel that night. The next evening, on Vigoreaux's show, Clemente looked into the camera and urged his fellow Puerto Ricans to help: "Bring what you can. Bring medicine ... bring food ... bring clothes ... bring it to Hiram Bithorn Stadium. Bring yourself to help us load. We need so much. I promise you, whatever you bring we will get there." Because he was Clemente, the people came. They walked through the heat and drove old cars and battered little trucks. The amount of supplies grew and grew. Within two hours, the first plane was on its way to Nicaragua. "We were walking out of the stadium together after a very long day of work," Vera Clemente recalled last week, "and next door they were building the new sports arena. We walked past all these construction machines and Roberto looked up at the top of the building and he said to himself, 'I wonder what will be its name.'" Today it is called the Coliseo Roberto Clemente, and a life-sized statue of Clemente keeps a lonely vigil at its entrance. "We had already sent some planes," Vera Clemente explains, "but there were bad reports about (Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle's people looting) and Roberto was very upset. He simply had to go to preserve what he sent and to protect the people delivering it. He could have done that, you know. He was, after all, Roberto Clemente." On the final morning of Roberto Clemente's life, Rudy Hernandez was in his bar and suddenly remembered the "mercy kettle." "It was a big iron pot and people were throwing money in it for the earthquake victims since the relief campaign began. They would have put money into any cause Roberto was behind," he says. "I called the house to find out what to do with it and Vera told me he was asleep, but I remembered he wanted it to go to Nicaragua to show the people how much we cared. "I told her I would send Manny (Sanguillen) to the airport with it. The day before, Roberto had stopped by the bar and I remember I urged him not to go because it would be New Year's Eve. But he said, 'If I don't, who will?'" "I let him sleep that morning," Vera says. "You know he had insomnia, and I felt he needed the rest, so I went on cooking his lunch while he was in the bedroom. The house was quiet. The children were at my mother's. I waited for a call from the airport to tell us when the plane would be ready. It was late." As Vera pieces together the hours that will live within her forever, the expanse of Rio Piedras is visible in the picture window behind her. In the corner of the dining room there is a plaster of Paris statue of her late husband that had once been on public display. It wears his old Pittsburgh Pirates uniform. She has walked a fine line between honoring his memory and creating a shrine. The pictures that tell the story of their life together. This is no museum. It is the place they called home. "When the call came from the airport," she says, "I awakened him and we had lunch. We were sitting there and I said to him, 'You know, Roberto, this was a strange year for us. On many days of importance to us, we were not together. And now it is the last day of the year ... New Year's Eve ... and we will not be together again.'" "And then he said something to me of great importance. He said, 'Well, we both cannot go. We have guests coming to celebrate the new year and one of us must stay. But the thing is you should not worry about this day. It is only one day in our lives, and for us - with love - every day is the same. We will have them for many years. " 'But I promise you one thing. If anything - anything at all - is wrong with this plane, I will cancel the trip.'" There had been trouble with the plane. It was a DC-7 and it was overloaded. The first time they tried to take off, they had to return for more work on the engines. Vera did not know this until much later. At the airport, she said goodbye to Roberto and then went down to the terminal's other end to wait for their guests from Pittsburgh to arrive. "I remember," Vera says, "I shook hands with the mechanic and the pilot and the plane's owner who were all going and who died with Roberto. Finally, I said goodbye to Roberto. "He was standing in the doorway of the plane. He gave me what I thought was a very sad and a very deep look. I never forgot that look. I saw many things in that look that seemed to say, 'I would like to stay but I have to go.'" Vera paused here, but there were no tears. Still, a shadow seemed to cross her face and it spoke of a mixture of love and pain and sadness. The retelling of all this was not an easy thing for her. "I had been with him the morning the first relief plane took off," she says. "But now it was different. I felt a tightness in my chest. Do not ask me to explain it. I cannot." It was almost 8 o'clock when she and her guests arrived in Rio Piedras. The telephone was ringing. She ran, but by the time she picked up the receiver there was only a dial tone. Later, she would find out that Roberto had tried to call her and then had given her number to a mechanic named Delgado, saying, "Tell her we had to try a couple of times but now we are ready and I will see her soon." It was Delgado's call Vera had missed. Vera and her guests were going to Carolina to eat and then on to her father's home on Sixth Street, the home where Roberto first called on her father to ask permission to court Vera. But something drew her back to Hiram Bithorn Stadium. "It is where the relief campaign was headquartered," she says. "I had to look in there." That's where Vera Clemente was at 9:33 p.m., surrounded by mounds of clothing and boxes of food. She had no way of knowing that her husband had just died. "We were in the bar," Rudy Hernandez recalls, "and it was typical. All over the island, parties were just getting started. Then I got a call and we turned on the radio and in that instant the music stopped everywhere on this island." The trouble had been with the port side engines. Most of the afternoon mechanics had worked on them. Most people believe it was those engines and/or the overload of cargo that caused what followed. Just 90 seconds after takeoff, a single, ominous statement from the pilot came over the plane's intercom: "We are coming back around." There were two explosions, one in the air and the other when the plane hit the water. Shortly after midnight, in the home where she had agreed to marry Roberto, Vera heard the news. "So much happened that night. So much happened since," Vera says. "Sometimes, when I am alone, I remember him telling me, 'The thing is, Vera, I would like to be remembered one day as a man who gave all he had to give.'" She pauses. "My opinion is that he died the way he lived, helping on a mission that he imposed on himself. Nobody told him to go, but he did. That was Roberto." He was only 38 years old. 1. Puerto Ricans' respect for Roberto Clemente is so great, officials won't tear down this dilapidated public housing project with a mural of their homeland hero on it. 2. At the entrance to Coliseo Roberto Clemente in Puerto Rico stands a life-size statue of the baseball legend. The stadium was under construction at the time Clemente died in a plane crash in 1972. 3. Ex-player Rudy Hernandez: "I have never seen a time of sadness here like the one that began on the New Year's Eve when we lost Roberto." 4. Longtime Clemente friend Nick Acosta: "He will always be my measuring stick - as a player and as a person. He was our hero."

Remembering Roberto Clemente By HAL BOCK December 24, 2002 NEW YORK (AP) - Their major league paths crossed only briefly. Jackie Robinson was ending a Hall of Fame career crammed with sociological ramifications about the same time that Roberto Clemente was starting one every bit as critical. They shared one other similarity. Each of them believed there was more to life than runs, hits and errors. Robinson's philosophy is etched on his tombstone: "A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives." Clemente put it this way: "Anytime you have an opportunity to make things better and you don't, then you are wasting your time on this Earth." Robinson's impact as modern baseball's first black player was enormous. Clemente, the most important Latin player, did not waste his time. Thirty years ago Tuesday, as many of his friends and teammates were celebrating New Year's Eve, Clemente was at the airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico, loading rescue supplies on a prop-driven DC-7 bound for earthquake victims in Nicaragua. Three thousand people were dead. Thousands more were injured. Clemente already had flown there once to help the survivors. Now, disturbed by reports that the black market had dipped into rescue supplies, he was returning. The flight had been delayed 16 hours. Clemente was impatient, eager to get on with the trip because he knew how desperately the people needed help. Waiting for a replacement plane would have been wasting time. So they took off, five men in a plane with a history of problems, overloaded with 16,000 pounds of supplies. Bound for eternity. Long before the doomed Nicaragua flight, Clemente had expressed humanitarian interests that stretched well beyond baseball. His dream was to establish a sports city in Puerto Rico and he dedicated himself to improving the lives of those from the island. He had a passion for his native land. That same passion led him to the plight of the people of Nicaragua and the fateful New Year's Eve flight. "At the time of the crash, my father was looking for land for the Sports City," said Robert Clemente, Jr. "He had talked to friends and people. It was his dream. After the crash, the governor donated 600 acres (240 hectares) of land to build the city." Today, the Sports City stands 10 minutes from the airport, six baseball fields, a track, basketball and volleyball facilities. "It is his legacy," Clemente said. "His dream lives there." His father was an established star, equipped with a spotless resume that included 3,000 hits, a milestone achieved in the final game of the 1972 season. There were four batting championships, a career .317 average and grudging acknowledgment that he was probably the best right fielder of his time. At 38, he planned to play one, perhaps two more years. "He was tiring of the travel," his son said. "He was talking about retiring. He felt he was missing too much time with us." As difficult a time as Robinson experienced as the first black player, Clemente found much the same resistance as the first Latin standout. There were other Hispanics before him but never one who demonstrated his skills. And when he began to emerge as a star, there were whispers. He didn't always play hard. He was a hypochondriac. He was trouble in the clubhouse. Nellie Briles remembered hearing all that when he pitched for the St. Louis Cardinals. When he joined Pittsburgh in 1971, Briles discovered a different Clemente. "You never fully appreciate a player until you see him play every day, see how he goes about his work, see how he goes about supporting his teammates and what kind of leader he is," he said. "He never felt he got the recognition of the others who were in the limelight, the Mantles, the Aarons the Mayses. Roberto had such an intense pride, he felt he belonged in that select company. "You never fully understand the impact that a player like Roberto has. You heard that he never was all that outgoing as far as the public is concerned, but he was greatly respected by his teammates, as I found out. He was a player's player. When I saw him every day, I fully realized what a great player he was and what a leader he was." The other Pirates already knew that even if the rest of baseball did not. In 1971, Clemente would make the ultimate statement in the spotlight of the World Series. "Now they will see how I play," he said. And they did. "He knew that was his opportunity," his son said. "He was ready for it." Clemente grabbed that Series against Baltimore by the lapels and shook it hard. He had 12 hits in 29 at-bats including two home runs, two doubles and a triple. He drove in four runs and scored three, and put that rifle arm on display from right field. "All the things he worked so hard for, all the lack of recognition, not only about Roberto but about Latin players in general, all the injustices he felt he had to suffer, all those things were finally put to rest with seven days in October," Briles said. "(After that), I don't think he had the demons he had earlier in his career. (Before), he was still fighting the segregation issue, fighting language and cultural barriers, the small market vs. big market recognition, there were a lot of barriers that he was fighting." Those barriers were set aside in 1971 and Clemente was a man at peace with himself a year later when he found other people who needed help.

Clemente's Legacy Thirty Years After His Death, Former Pirates Star Is Still Making An Impact On Latin Players, Children BY KEVIN BAXTER December 31, 2002 COMMANDED RESPECT: Roberto Clemente was known for more than his baseball skills. He was also a humanitarian who died trying to get money and relief supplies to earthquake victims in Nicaragua. New Year's Eve parties were already in full swing when the DC7 rolled away from the cargo terminal at San Juan International Airport, pointed its nose into the wind and lumbered down the runway. The plane, overloaded with relief supplies for victims of a deadly earthquake in Nicaragua, was on a mission of mercy. Its five passengers, including Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Roberto Clemente, counted on fate to be kind. On this night, however, fate was not in a kindly mood. Minutes after lifting off and with the airport still in sight, the plane suffered catastrophic engine failure and plunged into the murky, shark-infested waters of the Atlantic Ocean. All five passengers died. That was 30 years ago tonight. So this evening, as she has done on each of the past 30 New Year's Eves, Vera Clemente will drive to a desolate stretch of Puerto Rican coastline and remember her late husband by praying a rosary and tossing flowers into the sea. And in a few weeks, thousands of young men from throughout Latin American will honor Clemente's legacy in another way: by showing up at major-league training camps in Arizona and Florida ready to play baseball. ''No question he inspired so many Latin players, especially players from the Caribbean area, to work hard and to reach the major leagues,'' says Hall of Fame broadcaster Jaime Jarrín, who has called Dodgers games in Spanish since 1959. ``He was very proud of being Latin American. He was very proud of being Puerto Rican. He knew that he had a responsibility of opening the doors for other players.'' Thanks in large part to Clemente, those doors are wide open now. In the three decades since Clemente's death, Latins have gone from a novelty to the dominant force in professional baseball. When Clemente made his debut with the Pirates in 1955, there were just 14 Latin-born players in the majors. Today, nearly a third of the players on baseball's 40-man rosters are of Hispanic origin. Last season, there were more players named Rodríguez (48) and Martínez (47) playing organized baseball than there were Smiths (38) and Joneses (31). And the Latin influence in baseball today goes beyond mere acceptance or sheer numbers, especially in the American League, where four of the past seven MVPs were from Latin America and players of Hispanic origin topped the AL in batting average, home runs, RBI, runs scored, hits, doubles, stolen bases, earned-run average, strikeouts and saves last season. His widow says Clemente was instrumental in creating the climate that allowed that to happen. ''Roberto, in his time, always fought, like Jackie Robinson, to erase the color barrier in the major leagues,'' says Vera Clemente, speaking in Spanish from the Roberto Clemente Sports City in Carolina, Puerto Rico. ``Roberto fought to protect Latins. ``At that time, [they] had it tough because of the discrimination. But thank God that over the years Roberto and the others were able to overcome. That opened the doors for the players of today.'' And not just the doors to the clubhouse. Clemente also forced opened the doors to the manager's office and the front office as well. Omar Minaya, the Montreal Expos' general manager and the highest-ranking Latin in baseball, says he wouldn't have his job if Clemente hadn't come along first, demanding equal rights for Latin Americans in baseball. ''One of the reasons that I am here is because of the impact that he had as a player, but also the impact that he had as a person and the legacy he left behind,'' says Minaya, a Dominican who keeps a photo of Clemente in his office. ``He would talk about issues that are beyond the playing field. He transcended baseball.'' Adds Giants manager Felipe Alou, one of three Latin American-born managers in the majors: ``There is no question about the influence of Roberto Clemente. He was a guy who, at a time of great restrictions, when there were things that players didn't say, Roberto Clemente said them. ``There were things that Latin players would never dare say or challenge that Roberto Clemente, from his position of being a super-super star, went out and denounced or wasn't afraid to talk about.'' The discrimination Clemente encountered took many forms, from being refused entry into hotels and restaurants with the rest of the team because he was black to being criticized as a malingerer and mocked for his broken English by a press corps that quoted him as saying things like ''I heet home run'' and ``how I gonna run when I still on ground.'' Clemente thought that made him sound childish and uneducated when the real problem was none of the writers spoke Spanish. But the way Clemente died has probably had more to do with cementing his legacy than his .317 career batting average, 12 gold gloves, 3,000 hits and four National League batting titles. After a massive earthquake struck Nicaragua just after midnight Dec. 23, killing 6,000 and destroying nearly two-thirds of the structures in the capital of Managua, Clemente joined a campaign to collect money and relief supplies in Puerto Rico. Just weeks earlier, Clemente had been in Nicaragua coaching in an amateur baseball tournament. While there, he befriended a boy who had lost both legs in an accident. Clemente solicited funds to buy the boy artificial limbs. When reports began to surface that officials of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza's National Guard were stealing relief supplies intended for earthquake victims, Clemente ignored the pleas of his wife and teammates and insisted on accompanying the Puerto Rican donations to Managua to supervise their dispersal. The plane first taxied to the rain-soaked runway at 6:38 p.m. -- nearly 15 hours after its scheduled 4 a.m. departure -- but returned to its hangar 21 minutes later for new spark plugs and more than an hour of mechanical work to both right-side engines. Clemente was growing impatient by the time the four-engine, propeller-driven transport finally headed back to the runway nearly 5,000 pounds overweight. The DC7 needed more than 8,000 feet of the 10,000-foot runway to reach takeoff speed and climbed ''very slowly,'' according to witnesses quoted in a months-long investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board. At 8:22 p.m., the plane lumbered into the air. But 75 seconds later, Miami-based pilot Jerry Hill radioed the airport that he was ``coming back around.'' Seconds later, the plane crashed into 125 feet of water about 1 1Ú2 miles off the Puerto Rican coast. News of the crash spread quickly. Hundreds of people made their way to the beach to search for survivors. But Hill's body was the only one ever recovered. Among the many ironies in Clemente's death is the fact that he raised much more money for the relief cause in death than he was able to solicit while alive. Hundreds of thousands of dollars -- including a $1,000 check from then-President Richard Nixon -- poured in overnight to continue Clemente's work in Nicaragua and to bring to reality his long-held dream of a sports camp for children in Puerto Rico. Within days, the baseball writers association -- including many writers who had openly mocked Clemente's accent and penchant for injuries just years earlier -- voted to ignore the mandatory five-year wait and induct Clemente into the Hall of Fame, making him the first Latin player to be enshrined. Lou Gehrig is the only other player for whom the five-year wait has been waived. Hurdles that had long stalled plans for a sports city in his hometown of Carolina, where Clemente grew up poor in a barrio called San Anton, also disappeared overnight. The government of Puerto Rico set aside more than 300 acres of land, and donations from the U.S. funded much of the construction. Today, the $13-million center, which took shape shortly after Clemente's death, sprawls over 600 acres and features seven baseball diamonds, three indoor basketball/volleyball courts, a pool, 10 batting cages, two playgrounds and a track stadium. The center serves 200,000 people a year, many of whom are escaping homes ravaged by drug and alcohol addiction. Sports city alumni include major-league stars Carlos Baerga, Ivan Rodríguez, Rey Sanchez and Ruben Sierra, all of whom return on a regular basis to work with the children. Their presence is perhaps the biggest part of Clemente's legacy. ''Roberto loved children,'' says Vera, who runs the sports city with a board that includes son Luis, Sharon Robinson, daughter of Jackie Robinson, and former presidents of both the American and National leagues. ``He was making plans to construct a project like this where there would be facilities for all the sports, and other alternatives as well. Because not all kids like sports. In the case of Roberto, he liked music. He liked working with ceramics and plaster. And he was a poet. ``I think Roberto is very satisfied and happy with what's happening. After all these years, we're winning the battle.''

|

----------

----------