|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. The Washington Post Spanglish: Pop Culture's Lingua Franca By Teresa Wiltz January 26, 2003

It's a moment of high drama, the kind of drama of which Tony Soprano would heartily approve. Except that in this instance, the players are brown, the mob is Mexican and the moment of truth gets played out with a radically different sabor: It's showtime. As in show-me-and-then-I'll-give-you-the-money time. "Ensen~ame la carga," a mobboss orders his flunky, rubbing his hands with anticipation. "Ensen~amela." He's an excitable sort, and the very idea of la carga has him so geeked, he's literally jumping up and down. "A ver . . . A ver que tienes! A ver que tienes!" The flunky obeys, and opens up his SUV. And out comes tumbling la carga: the bloody and bullet-ridden body of a DEA agent. Even if you don't habla español, it doesn't take a linguist to figure out what's going on in "Kingpin," NBC's upcoming drama about a Mexican drug lord. Which is exactly the point these days, as increasingly, snippets of Spanish, sometimes translated but often not, crop up on the big and little screen. As the U.S. Latino population expands to 37 million, on-screen life is gradually changing to depict la vidalatina. And that means that Spanglish -- the mixing of Spanish and English -- is the featured act these days in mainstream Hollywood fare, from "Traffic," where a substantial part of the dialogue was in subtitled Spanish, to John Sayles's almost-all-Spanish "Men With Guns," to both "Spy Kids," where Spanish words were tossed about, to Spike Lee's "25th Hour," where untranslated dialogue floats around like background noise, to John Leguizamo's "Empire," to "Real Women Have Curves," in which the Latina protagonist is fluent in both California-ese and her parents' native tongue. On the smaller screen, there was the mournful -- and controversial -- chihuahua who crooned, "Yo quiero Taco Bell." But now, there is "The George Lopez Show," where the Chicano comic peppers his speech with "o{acute}rale," while on PBS's "American Family," starring Edward James Olmos and Raquel Welch, Spanish is an integral part of the family's Mexican American culture. For preschoolers, there's Nickelodeon's bilingual "Dora the Explorer," aka "Dora la Exploradora." On "CSI: Miami," the hip forensic crew will throw in a word or two while questioning witnesses, just to let everyone know they're down. (Or maybe it's just to cue in viewers lest they confuse "CSI: Miami" with the other "CSI" set in Las Vegas.) The linguistic revolution isn't limited to the screen: Lalo Alcaraz's comic strip, "La Cucaracha," uses Spanglish to poke political fun at both Anglos and Chicanos. In literature, there was Chicano poet Alurista and the Nuyorican Poets Cafe out of New York, who set the stage for other bilingual writers such as today's Junot Diaz. His highly acclaimed short-story collection "Drown" incorporated elements of Spanish, as does Sandra Cisneros's "Caramelo." Then there's Puerto Rican poet Giannina Braschi, who recently published her all-Spanglish novel, "Yo-Yo Boing! (Discoveries)." Music groups such as the Los Angeles-based Ozomatli frequently sing in Spanish and rap in English, while rapper N.O.R.E. boasts in his latest hit about being "half Spanish, all day arroz con pollo." Spanish is hip, a flavoring, a punctuation, a way to express cultural pride -- and an awareness of the rapidly changing U.S. landscape. "Latino culture is moving from the periphery to center stage," says Ilan Stavans, author of "Spanglish: the Making of a New American Language," and professor of Latin American and Latino culture at Amherst College. "Mainstream Americans are absorbing this and thinking that it's hot. I've even seen Spanglish Hallmark cards. . . . This Spanglish thing is very cool, even if you don't speak it. It makes you attractive to younger people, to a particular audience that's out there and that corporations want to address." Which means that, at times, the use of Spanglish is nothing more than a marketing move, a wink-wink, nod-nod way to acknowledge the nation's new reality without doing a whole lot more. There are many examples, after all, of resistance to issues such as bilingual education -- never mind that the vast majority of the Americas' population, North, South and Central, is Spanish-speaking. Tossing a few Spanish words into the mix becomes a shorthand, a quick way to indicate other. There's a fine line between celebrating a culture and pimping it. "I find it just interesting that certain elements of me are fit for consumption but certain aspects of my culture are not," says the Dominican-born Diaz, who is now working on his first novel. "I see the language more than I see the people, the complicated space we inhabit in the culture. . . . I'm not sure the appearance of Spanish means much for the masses of Latinos who are struggling for social justice or . . . just trying to have better lives." In Hollywood, there are few Latinos who have the power to greenlight a project -- and therefore the power to control Latino images. The few who do have tried to increase representation. Showtime's "Resurrection Boulevard," one of the first TV dramas to be written, produced by and star Latinos, put some 500 Hispanic actors to work during its three-season run -- more than all four networks had done in the previous 10 years, according to Alex Nogales, president of the National Hispanic Media Coalition. (The show has since been canceled because of poor ratings.) Gregory Nava produces "American Family," while Moctesuma Esparza, who produced "Selena," is working on a project about activist Cesar Chavez. Director Richard Rodriguez is careful to cast his "Spy Kids" in a Latino milieu. "The George Lopez Show" made it to ABC, thanks in large part to the A-list pull of executive producer Sandra Bullock. Alcaraz, the comic strip artist, recalls the time he was hired as a writer to work on the short-lived Fox comedy show "Culture Clash." At first, he says, almost all the writers were Latinos. By the end, he says, there were only two: Alcaraz and Josefina Lopez, the playwright who wrote "Real Women Have Curves," and co-wrote the screen version. "In the end, I was just kind of translating things," Alcaraz says, adding that he wasn't too disturbed by it. "I was like, 'Ahh . . . that's showbiz.' " When it came to his sitcom, stand-up comic Lopez had no illusions about showbiz: He wanted to create a mainstream sitcom about a family that just happened to be Latino. And he wanted it to be stereotype-free. So he cast Latinos who spoke unaccented English. He wanted no bad accents, no rapid-fire, hands-on-hips harangues, no "I'm so upset, and then go off into 'Que tal loca no sabes . . . ' " So his first season, Lopez says, he dropped only one bit of Spanish into the mix: He called his TV grandmother a "crazy old vieja." "My plan," he says, "was to get renewed, and then start dropping my o{acute}rales. Now I feel comfortable dropping it on the American people. "We've been invisible for so many years. I want to bring what's really out there, culturally, with language. Latinos have infiltrated every aspect of the culture. It's a connection that we are making when TV is not as milquetoast as it's always been. It's like food -- it adds flavor." But sometimes the flavor can leave a bad aftertaste. Desi Arnaz, with his impeccable suits and rapid-fire Spanish, introduced much of Anglo America to Cuban culture on "I Love Lucy." In the late '70s, U.S. audiences tuned in briefly to the bilingual "Que Pasa, USA?," a PBS sitcom about a Cuban American family. (And starring the actor Steven Bauer, back when he was known as "Rocky Echevarria.") But now, critics say, things haven't progressed much beyond the stereotypes of Pepino in "The Real McCoys," reducing the Spanish language and Latino culture to a caricature. Today, with our nation's endless fascination with cops and robbers, that caricature is the Latino as drug dealer, whether it's in "Traffic" or the remake of "Shaft," in which the Dominican baddie is portrayed by African American actor Jeffrey Wright. "If we're not maids, we're [expletive] drug dealers," Diaz says. "It's no accident you're going to find the first usage of Spanish" in drug films. Which is why some Latinos are taking issue with the upcoming "Kingpin," NBC's limited-run drama that debuts next Sunday. "Kingpin" tracks the life of Miguel Cadenas (Yancey Arias), a Stanford-educated Mexican drug lord, as he struggles to reconcile his troubled conscience with the grimy reality of the family business. Set in both Mexico and the States, it is written primarily in English but leans heavily on the use of untranslated Spanish phrases. (Two key scenes in the series are shot entirely in Spanish and use subtitles.) "At a time when there's no balance of Latinos on television, for us, 'Kingpin' is not so great," Nogales says. "It's got superb writing, superb acting and great, great direction -- all the ingredients to be a great hit. But there will be a lot of problems with the Latino community." The show's creator is David Mills, an African American (and former Washington Post staff writer) who cheerfully admits that he speaks "not a lick" of Spanish. "That bothers me, absolutely," Lopez says. "It sends the wrong message. Would African American people love a show that depicts slavery in 2003? I don't think so. It's been seen, it's been done." Says Mills: "I'm not writing this as a Mexican. How can I? I don't know anything about Mexican culture. But I know about the human condition. . . . The breakthrough here is, this is a story about the condition of a man's soul. . . . Often in TV, to get that deeply in the psyche of a character, that character is white. It's pretty rare that a nonwhite character [gets that kind of attention]. . . . It's not a victory to have every Latino character on television viewed as an emblem of his ethnicity. It's a burden the actors don't want, and that I don't want." Except for Mills, all the show's writers are Latinos, but most of them don't speak fluent Spanish, either. Bilingual actors were cast; still, since the actors' heritage ranges from all over Latin America, a vocal coach was hired to help them with their Mexican accents. After all, there's a world of difference between the nuances of North-Mexican Spanish and, say, the Caribbean rhythms of Cuba or Puerto Rico. "I have a very good ear for dialogue," "Real Women's" Josefina Lopez says, and she's able to tell when the Spanish was written by a native speaker, or by someone who wrote it in English and then translated it into Spanish. "There's a rhythm to Spanish, especially if it's Mexican or Puerto Rican. I hear it a lot on TV when they do it, and I say, 'No, they missed the beat.' " Still, she says, it doesn't bother her when non-Latino writers take on her language and culture. "As long as they get the rhythm right, I'm happy that they're doing that. It shows a respect for our language and our culture."

|

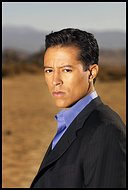

Yancey Arias stars in NBC's "Kingpin," an English-language show featuring unsubtitled Spanish dialogue.

Yancey Arias stars in NBC's "Kingpin," an English-language show featuring unsubtitled Spanish dialogue.