|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMES Spanish Harlem On His Mind By ED MORALES February 23, 2003

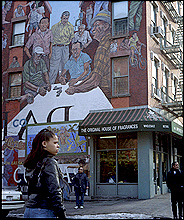

A mural by the prolific James de la Vega. "I have a love-hate relationship with this place," he says. [Rebecca Cooney for The New York Times] ---------- EL Barrio. In my childhood its mere mention conjured all kinds of feelings, from a kind of reverence for proud beginnings to my parents' wariness of its slow descent into hard times. It was a magic Spanish phrase that fell easily from my father's lips, a reference to a place that curiously seemed to belong to us, even though New York didn't belong to us. As more of us moved to various corners of the Bronx, El Barrio increasingly became the source of authenticity, like the bacalaitos (codfish fritters) on 116th Street that were the closest thing to what you could get on the island. As I grew older and the neighborhood's mean streets became even meaner, I was still in awe of its self-assured Latin style. Even in my feeble Santana fan worship I knew that what "Oye Como Va" talked about ultimately went back to Tito Puente and the streets of El Barrio. Sharkskin-suit-wearing mambo men spinning leggy lace-draped women at the Park Palace on 110th and Fifth Avenue lurked in my subconscious. Multicolored Latin men standing their ground against turf invaders, wearing T-shirts and pegged pants, with an angry curled lock of defiance spilling onto their foreheads, haunted me in my exiles in the Bronx, New England and the Lower East Side. I could almost hear the slow boleros from rooftop parties, the anomalous screech of roosters on fire escapes, holding me in the grip of the peculiar alchemy created by tropical people shivering in poorly heated tenements.

"The Spirit of East Harlem," a 1979 mural at 104th Street, known locally as Mural Row. [Rebecca Cooney for The New York Times] ---------- The late theater director and promoter Eddie Figueroa, who lived in the projects at 114th and Lexington Avenue, once declared that wherever he called home was the embassy of the Spirit Republic of Puerto Rico, and for the first time I understood El Barrio as a sanctuary of an idea, an identity. It was an imaginary homeland that I shared with countless other displaced souls, U.S.-entrenched Puerto Ricans in search of being Puerto Rican. Today, although Puerto Ricans are still the city's most populous Spanish-speaking group - of the 2.2 million Latinos, 830,000 are Puerto Ricans - we can sometimes feel like an afterthought in the Latin New York we all but created. WHEN the Metro-North trains come rumbling like massive conga drums out of the Park Avenue tunnel at 96th Street and toward the northern viaduct, they draw attention to one of the enduring symbols of racial and class division in New York. It's as if they're saying: Welcome to East Harlem, where hip-hop and salsa trump classical, and prime real estate gives way to inner city. The architectural necessity of the viaduct, built in the 1840's, is the primordial source of the real estate mantra: "Manhattan below 96th Street." But now, whispered buzzwords of gentrification like Upper Yorkville, Carnegie Hill North and SpaHa (for Spanish Harlem), are creeping up from the south. The specter of new luxury high-rise developments with tony names like the Monterrey and Carnegie Hill Place are pushing back the ghetto flavor. The Spanish Harlem of the mind, dotted with the world's greatest cuchifrito stands (fried Caribbean snacks), stickball clubs and old-school piragueros, men who sell flavored ices from pushcarts, is threatened with extinction. The changing face of East Harlem is due not only to the real estate charge from south of 96th Street, but also to a surge of Latino immigrants. That new presence is personified by Valente Leal, a 14-year-old immigrant from Mexico who has lived in East Harlem for the past eight years.

Puerto Ricans who pioneered El Bario wonder what will become of their beloved adopted homeland. [Rebecca Cooney for The New York Times] ---------- Valente has a bushy spiked punk haircut, likes hard rock bands like Korn and Slipknot, is an occasional painter and wants to be a doctor. And Valente's got a theory about why so many people from south of 96th Street are moving in. "Ever since 9/11 there's all these people from downtown around here," he said, wide-eyed. "I think they got scared or something." So, as the strip on Lexington between 104th Street and 96th morphs from Barrio to boho periphery, a loose confederation of mostly Puerto Rican politicians, activists and residents is trying to make a stand to preserve the area's Latino identity. Rafael Merino, a graphic designer who grew up on the Lower East Side and recently moved from Williamsburg, thinks what's happening uptown is bigger than mere nostalgia. "It's not about Latinos losing El Barrio, it's about New York City losing El Barrio," said Mr. Merino, who lives on 116th Street. "This is one of those diverse gems that makes the city what it is." ALL of this flux, all of these questions - about gentrification, about the future, about whom El Barrio truly belongs to - sent me back to the neighborhood's streets, where the ambivalent dance of development is played out. For me, the son of Puerto Rican parents who came to Manhattan during the late 1940's, East Harlem, or El Barrio, as we called it, stirred mixed emotions. It was where my parents suffered the early indignities of American dream-searching, a grimy tenement-land they escaped for the relatively pastoral Castle Hill in the Bronx in the 1960's. But even as I left the Bronx for the East Village and, finally, Brooklyn, El Barrio had an undeniable allure for me. I craved the memories of the smells and sounds of then-exotic Caribbean vegetables at La Marqueta, the indoor market at 115th Street and Park Avenue, and the salsa jams throbbing from the Casa Latina record store on 116th Street. Six years ago, when I went to the funeral for my uncle Angel Luis, one of the last of my relatives to still live there, I felt as if I had a claim to El Barrio's mythology. The Barrio of bodegas, botanicas and bomba y plena (traditional Puerto Rican folk music) came into being in the 1950's, when the Puerto Rican migration peaked. The neighborhood went into a steep economic decline and depopulation in the 1970's, and East Harlem's Latino identity began to take on an ephemeral quality. "Some of us, if they were lighter skinned, gravitated to a white identity," said Aurora Flores, a publicist and community activist. "Those who were darker gravitated to a black identity, so it's become important to us to define our identity." Ms. Flores is the M.C. of a weekly Thursday gathering called Julia's Jam, held at the Julia de Burgos Cultural Center at 105th and Lexington Avenue. Recitations by single mothers and schoolchildren take precedence over slam poets, and the evening culminates in a free-form jam session by the bomba y plena group Yerba Buena. Administered by the arts organization Taller Boricua, the de Burgos Center is part of a "cultural crossroads" envisioned by a Taller co-founder, Fernando Salicrup, a painter and a Barrio homeowner. Born and raised in the neighborhood, Mr. Salicrup is a mentor to an emerging group of young artists, writers and musicians who are moving back to the neighborhood. "I learned to be Puerto Rican in this community," Mr. Salicrup said. "I didn't learn it in Puerto Rico." On any night, El Barrio, a true cultural crossroads, comes alive. And while it still holds on to a Puerto Rican identity, it is also infused by new blood. As I tool around Lexington, I can run into Erica González or Melissa Mark-Viverito, co-founders of Women of El Barrio, a political group, or Mariposa, a poet, scribbling away in her notebook. When I slide into a booth at La Fonda Boricua (Boricua is an affectionate name for a Puerto Rican) on 106th Street, surrounded by paintings by Latinos, and feast on rice and beans, I feel as if the Latino renaissance that could have happened in the East Village 15 years ago is happening here. But Tato Torres, a founding member of Yerba Buena and conscience of the area's cultural renaissance, warns me: "This art thing is a double-edged sword. It's easy to become the exotic Latino-flavored thing and make the place chic for outsiders. There's already been some animosity between Barrio natives and recent arrivals like me." I ponder his words, and remember how artists were the leading edge of a rent escalation that displaced thousands of Puerto Ricans east of Avenue A as I head further down Lexington, to the intersection of the new and old East Harlem, to Galeria de la Vega, run by a local artist. James de la Vega is a hybrid between a street kid and an Ivy League-educated guerrilla performance artist. He surfs among the personas of mayor of the block, eccentric artist and entrepreneur with relative ease. Because he has run tours of El Barrio for outside agencies, scrawls incendiary slogans on the sidewalks and occasionally flaunts a huge Afro wig and black leather pants, he is the focus of some controversy. "I have a love-hate relationship with this place," said Mr. de la Vega, who grew up in the neighborhood the son of Puerto Ricans. "Some of the things I write on the sidewalk are a little tough for the people here." And he admits that he likes to provoke people with phrases like "We walk amongst each other in a deep dream committing small acts of violence against one another." Some people in the neighborhood have taken such offense to Mr. de la Vega's act that they have painstakingly defaced most of his murals scattered around East Harlem. "As much as I like to promote the concept of this being Spanish Harlem, I also feel that we have to connect with the world in a bigger way," he said. "But there's an element here that doesn't feel I'm doing the right thing, so I'm forced to rethink myself sometimes." A quick stroll west, under the stone arches of the northern Park Avenue viaduct and through the projects on Madison, brings me to El Museo del Barrio, which has been challenged by a local group called Nuestro Museo Action Committee that feels the museum, founded by local Puerto Rican activists in 1969, has neglected the neighborhood to focus on the high art of Latin America. Tony Bechara, the museum's chairman and a painter from Puerto Rico but not El Barrio, gave me a thorough tour, beaming with pride about last summer's wildly successful show of the Mexican painters Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera and the permanent exhibition about the Taino Indians, the ancient indigenous people of Puerto Rico. "Our direction has been toward inclusivity," he said, explaining that the museum's limited space restricts the number of community artists they can show. Next month, El Museo will feature the Puerto Rican artist Rafael Tufiño, but the Nuestro committee continues to lobby for local representation on the board. Tato Torres of Yerba Buena recently sent an e-mail message to committee members including a Web page from Citysearch.com, which listed El Museo with the pull quote (since changed): "This little museum isn't just for Boricuas anymore." It seems a harmless sentiment, but it represents an attitude that makes Puerto Ricans angry. In the larger world of Latinos we (and to an extent Dominicans, who dominate Washington Heights) are underdogs in the Latino identity game, easily marginalized by swanky displays of cultural capital that Mexicans and South Americans can summon. But, as Mr. Torres says, El Barrio's Mexicans don't necessarily profit from Kahlo chic, and are crucial to the future of the neighborhood: "In El Barrio we have to find those threads that bind. We have to find what will unite us, whether we're Colombians, Mexicans, Dominicans or Puerto Ricans." MY father, who lived on First Avenue near 114th Street in the early 1950's, likes to tell the story of a friend from his hometown in Puerto Rico who came to visit him after immigrating to Chicago. "He adopted some of the Mexican customs they have over there and came to New York wearing a flashy zoot suit," he said. "He was late, so when I went to check on him, I found him bloodied in the hallway. The Italians had beaten him up." Forty years later, the Mexicans truly began arriving, and after enduring their own beatings from local groups, they settled in to become hard-core residents of El Barrio. The main drag of 116th Street offers several Mexican restaurants, record shops blaring mariachi and rock en Español, and a store filled with fútbol jerseys. Leaders of both the Puerto Rican and Mexican communities fall all over themselves to express solidarity, but there is little overt interaction. On the surface, the differences are clear: the jukebox in El Paso Taquería favors Mexican corridos and cumbias over salsa and merengue, and the street kids align themselves in camps that prefer the Mexican rockers Jaguares or the Puerto Rican rapper Fat Joe. But in the public schools, the teenagers are creating a new Latino melting pot. Alberto Medina, a Puerto Rican classmate of Valente Leal's, says: "I play soccer. I eat tacos, my uncle married a Mexican and my other uncle married a Dominican." The Mexicans bring such a feeling of new energy that they give some locals the incorrect impression that they are the new majority Latino population, though they are third after Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, with a population of 196,000. The neighborhood also contains sizable populations of African-Americans and Italian-Americans. Mark Alexander, who runs Hope Community, a development corporation that manages 1,400 housing units and oversees $125 million worth of real estate, points out that "many of the Latino residents of the past have moved out.'' "Last summer we had six free concerts in our garden," Mr. Alexander said. "The biggest hits were mariachi bands." Although many of Mr. Alexander's tenants are Latinos and his organization has commissioned work by local muralists like Mr. de la Vega, he doesn't see a Latino-centric future for East Harlem. "Gentrification is happening, regardless of what we do," Mr. Alexander said. So, whose casa will El Barrio wind up being? The political activist Erica González insists that "unless you actually make a commitment to create a permanent home here, you're looking at being pushed out." But these good intentions, coupled with the untamed forces of real estate, could displace even more people in the end. Perhaps the sprawling projects, which literally slice and dice the neighborhood, will make it hard to gentrify, and buy time for East Harlem to reshape itself in a way closer to its self-image: a place where conga drums and commerce can coexist. But it's going to take awhile, and the current economic slowdown will only reinforce what everyone in El Barrio knows, that things move a little more slowly in their neighborhood. Maybe these are just the ramblings of a nostalgia-obsessed migrant of the new Latino diaspora. But when I sit at a table at La Fonda Boricua with a plate of bistec encebollado (onion steak) with fried plantains, I feel as if I have found the center of my universe. And as I make fleeting eye contact with new and old acquaintances, and total strangers who look like cousins, aunts and grandfathers I've never met, I know I'm part of something that will never completely disappear. El Barrio is where strangers will still say hello to you on the street, where people are trying to hold onto a sense of melody and rhythm that has defined them for half a century. I can hear it echoing on these streets - it's a song that calls me back, like a sailor to his old home port. It's the song of Harlem, Spanish Harlem. Ed Morales’s most recent book is "Living in Spanglish: The Search for Latino Identity in America," to be published this month in paperback by St. Martin’s/Griffin.

|

----------

---------- ----------

---------- ----------

----------