|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE MIAMI HERALD Puerto Rican Singer Wraps His Rap In Traditional Salsa BY JORDAN LEVIN July 1, 2003

In an era when packaged pretty boys are the salsa standard and rappers need those six-pack stomachs to hold up all their gold chains and designer gear, a wild-haired, gravel-voiced 31-year-old Puerto Rican artist has blown up with a complete disdain for formula. Instead Tego Calderón is taking his island's musical and cultural roots in a fresh direction: mixing salsa and African-rooted bomba with rap and dancehall, live musicians with DJ tracks, '60s slang with the latest barrio lingo. Released in December by independent White Lion, Calderón's debut, El Abayarde (the name of a small, stinging ant native to Puerto Rico that's also Calderón's artistic tag), has hit it in Puerto Rico with both teenage fans of American hip-hop and their salsa-loving grandparents. It has sold more than 150,000 copies in Puerto Rico and 70,000 copies on the mainland as an import. It's all over radio on not just the island, but in New York and other Puerto Rican populated stateside cities. It will be released for general distribution in the United States today by BMG U.S Latin. Calderón rocked the Billboard Latin Music Conference in Miami Beach in May with an electrifying combination of rhythm and musical energy that was the only fresh performance in an exhausted industry event. It was a triumphant return to a place that was briefly home for the former Miami Beach Senior High School student. ''Salsa has been losing its strength -- it lacks reality,'' Calderón said a few days later. ``It's not about music anymore, but about business . . . For me the same thing is happening with rap. I don't sense any respect in the music for its origins.'' `A LOT OF RACISM' Calderón frequently tackles the thorny subject race. In Loiza, a track that opens with the African-sounding drums of bomba, he accuses the Puerto Rican establishment of racism. ``They want to make me believe / that I'm part of a racial trilogy / Where everyone in the world is equal . . . You traded in chains for handcuffs.'' ''My music is strongly influenced by my African heritage,'' Calderón says. ``On the island there's a lot of racism. It's not as marked or open as it is in the U.S., but it's just as bad because nobody's up front about it. But I've hit on this in a really aggressive way, and people are proud of me for saying it. ``I'm not a cute guy, and I'm competing against all these pretty voices. But I come the way I am, and musically I'm doing something different.'' Individuality and integrity have been key to Calderón's success, says Bryan Meléndez, program director of New York's Latino Mix 105.9 FM, who put the rapper in the station's mix. ``He's one of these guys with a unique charisma -- he's honest, downhome. He sings because he loves it.'' CROSSING GENERATIONS In Puerto Rico, reggaeton, which mixes reggae and rap, and hip-hop have surpassed the island's traditional salsa among its youth. Calderón has both ridden the wave and sent it in a new direction, crossing generations and giving fresh life to both genres. According to Billy Fourquet, vice president of programming for Spanish Broadcasting Systems in Puerto Rico, the proof of Calderón's appeal came at the Día Nacional de la Salsa concert in March, when Tommy Olivencia, a classic salsero whose songs Calderon has covered, invited him onstage. ``It was packed with salsa fans, ages 18 to 65, and everybody gave him a standing ovation. We couldn't believe what happened.'' Calderón credits his struggle to succeed with keeping him grounded. Calderon's mother is an elementary school teacher who taught him respect for language, and his father was a government worker who instilled his own love of salsa and jazz in his son. As he worked to make it in music, Calderon took jobs in construction, valet parking, and driving a taxi. He says the experience solidified the values that have sustained him and shaped his music. The thanks to God and gente that sprinkle his conversation have a sense of integrity that's lacking in the standard issue award-show platitudes. ''I do everything knowing that whatever you do comes back to you, all the good and the bad,'' Calderón says. ``I'm not into expensive cars and jewelry and all that stuff. I've changed the stereotype of the rapper, I do things my own way. I think a lot of the problems in society come from this false happiness that people believe comes with money. So with my music I try to teach the youth that these kinds of values aren't necessary. I want to teach them that they have value for who they are.'' In Puerto Rico, kids are wearing the Harlem Globetrotter gear Calderón sports, and using the words he re-invents from old slang. ''He's a benchmark now -- other artists sound like him,'' says Ileana García, research director for SBS. ROOTED IN RHYTHM Calderón, who attended a music school in San Juan, began getting into rap during the three years his family lived in Miami Beach, when he attended Miami Beach Senior High. He began rapping in English. When the family moved back to Puerto Rico and he heard others rapping in Spanish, he began making the music that made sense to him. But the urgent Afro-Caribbean rhythms of old-style salsa and folkloric bomba moved him as much as NWA and Public Enemy. He idolizes old-school salsa giant Ismael Rivera. To him the boasting, rhythmic improvisation of a classic sonero, or singer, segues naturally into the my-rhyme-tops-yours braggadocio of rap. ''It was easy for me -- I've always been a fanatic for Cuban and Afro-Antillean rhythms,'' he says. ''When I sing, I improvise in clave. I did it without meaning to -- my influences fused in me.'' On the last track of his record he raps over Tommy Olivencia's salsa classic Planté Bandera. ''I prove that salsa and hip-hop are in the same groove,'' he says. With his newfound clout, he is planning to make a record with some of salsa's big names from the '60s and '70s. In his performances, he aims for their musical exuberance -- there's a horn section, percussionists, and an old-style band director, as well as a DJ who works the turntables. ''I've done shows with just a DJ, but I don't feel the same,'' he says. ``The musicians give me the feeling that I'm doing something real. I think people respect that. It doesn't matter how good the DJ or the track is. Nothing beats live music.''

|

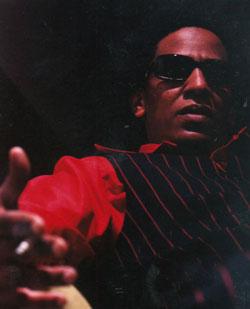

PHOTO: THE NEXT BIG THING?: Tego Calderon could be set for a Latin pop breakthrough.

PHOTO: THE NEXT BIG THING?: Tego Calderon could be set for a Latin pop breakthrough.