|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. The Washington Post Killer Virus: In 1918, The Spanish Flu Swept The Globe. Today, It's A Grim Reminder In The SARS Fight By David Brown June 4, 2003

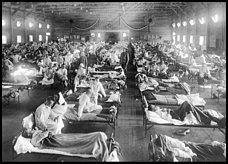

An Army hospital at Camp Funston in Kansas in 1918 is filled with the first victims of the Spanish influenza epidemic that eventually would kill at least 50 million worldwide. (National Museum of Health via AP) ---------- In the end, almost no place was spared. When the Spanish influenza virus circled the world in 1918, 1919 and 1920, it missed the Pribilof and St. Lawrence islands in the Bering Sea. Quarantines successfully protected the northern coast of Iceland and American Samoa. Undoubtedly a few other regions escaped, too, their good fortune undocumented. Otherwise, every place that man occupied, the virus visited. Few people alive today remember the Spanish flu firsthand. But the global epidemic lives vividly in the collective memory of medicine and public health. It's the distant mirror in which today's epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, is reflected. SARS is caused by a virus, as was Spanish influenza. Both are respiratory illnesses. Both are spread by coughing and close, but casual, contact. Both appear to have arisen from animal viruses that through mutation or genetic reassortment gained the ability to infect human beings. There are, of course, innumerable differences as well. SARS is deadlier, killing 10 to 15 percent of people who become ill. The Spanish flu exacted a highly uneven toll on different countries and ethnic groups. In the United States and a few other developed countries with good epidemiological records, the mortality rate was about 3 percent of people who became ill. In many other regions, good estimates are lacking, although among poor populations, it appears the death rate may have been as much as 10 times higher. What the Spanish flu had was extreme contagiousness and a global population almost entirely susceptible to it. What kind of devastation the SARS virus's particular combination of virulence and infectivity might ultimately produce is anyone's guess. The worst-case scenario, though, is not theoretical. It happened 85 years ago when -- according to the most recent calculations -- at least 50 million people died of the Spanish flu. SARS has not yet gone global in an epidemiological sense. Even though 29 countries have reported infections, only in China and Taiwan is it spreading in the general population. Elsewhere, nearly all cases are directly traceable to people who picked up the virus in the disease's Asian incubator, or had contact with people who did. The fear, of course, is that SARS will eventually spread stranger to stranger, without obvious chains of transmission, reaching so many places so quickly that public health officials will be powerless to contain it. That's what happened when Spanish influenza burst out of the American prairie in the late winter of 1918. An epidemic's portrait is painted by both the microbe and host. The Spanish flu's was painted not only by the peculiar, and still largely mysterious, characteristics of the 1918 virus, but also by the exigencies of war, colonialism and ocean travel. The epidemic may not have originated in the United States. Some experts today believe the virus came from China -- the birthplace of many flu strains -- and was detected here first simply because of better surveillance and record-keeping. Its first true victim has been lost to history. What is known is that on March 5, 1918, soldiers at Camp Funston, in Kansas, began coming down with influenza in large numbers. Military posts have always been fertile ground for outbreaks of contagious disease. Barracks bring people from many regions into close quarters under high stress. So it wasn't a surprise that ground zero of the pandemic was a military installation, or that the disease was next reported, on March 18, at Army camps in Georgia. The symptoms were mild, with few deaths. But the numbers of ill were high -- 2,900 cases out of 28,586 troops at the Georgia camps. The epidemic then hopscotched from one military post to another in the East and South, spilled into the civilian population, and reached the West Coast in late April, where an outbreak was recorded at San Quentin Prison. By then, however, it had already made a bigger and more fateful leap, across the Atlantic Ocean with hundreds of thousands of soldiers going to join the Great War. Outbreaks were noted at an Army camp in Bordeaux, France, and in the port city of Brest in early April. By the end of the month it was at the Western Front, in the American, British, French and German armies. In May it arrived in England with troops returning from France. That month saw an outbreak in Madrid and Seville that caused a total death rate about twice normal for that time of year. Spain was a neutral country during World War I. Unlike the belligerents in that conflict, it did not censor news reports, so the Spanish outbreak got wide publicity, ultimately lending its name to both the pathogen and the pandemic itself. Even at the time, however, experts realized the name "Spanish flu" was entirely misleading as an indicator of the germ's origin. The epidemic continued to move north and east, getting as far as Scandinavia and Poland. This "spring wave" did not reach Russia or sub-Saharan Africa, although it did get to India, arriving in Bombay on May 31 with a troop transport. Puerto Rico, part of the Brazilian coast, Indonesia, Australia and New Zealand experienced outbreaks in June. Influenza tends to be seasonal, as the virus survives longest in cool, dry air and is most easily spread when people are crowded together -- all conditions favored by winter. It was unusual for the first wave of the 1918 pandemic to last as long as it did, and not surprising when things slowed down in August. Then something happened. Microbes often adapt and change behavior while epidemics are underway. When slightly different strains are passing from person to person, a strain that kills its victims quickly, before they have time to infect others, may tend to disappear and be replaced by a strain that keeps its victims alive -- and transmitting disease -- for a longer time. Consequently, over the course of some epidemics the severity of illness appears to decline. But there also can be evolutionary pressure for microbes to become more virulent, if the change makes their hosts more infectious by, say, loading their mucus with germs or stimulating coughs and sneezes. How this push-and-pull played out in the summer of 1918 isn't known. Presumably a mutation crept into the virus. What is clear is that in late August a new outbreak of flu -- the "fall wave" -- began. The virus was as contagious as ever, but now more than 10 times as deadly. Between Aug. 22 and 27, the more virulent strain appeared on three continents -- Europe, Africa and North America. The near-simultaneity is a second big mystery. Perhaps a single mutant strain arrived, by chance, at the widely separate locales almost at the same time. Perhaps an identical deadly mutation arose independently in the three places. "All we can say is that the first hypothesis is improbable and the second extremely improbable," historian Alfred W. Crosby Jr. wrote in his 1976 book, "Epidemic and Peace, 1918." The three places -- Sierra Leone's capital, Freetown; Brest, France; and Boston -- were each ports crowded with people coming from distant lands. Crosby notes that of the 2 million American soldiers who went to France in the war, 791,000 landed in Brest. Boston had a shipyard, naval hospital and many agencies shipping war materiel. Freetown was the main coaling station for steamships going from Europe to southern Africa. From these coastal cities the new wave of infection raced to both virgin territory such as Africa and to areas only recently recovered from the spring wave, including Europe and America. "Influenza seemed to rage through sub-Saharan Africa as though the colonial transportation network had been planned in preparation for the epidemic," wrote K. David Patterson and Gerald F. Pyle, two University of North Carolina historians and geographers responsible for initiating much of the reanalysis of the pandemic in the 1980s. The newly built rail system in South Africa and Rhodesia was so efficient that Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) in the Belgian Congo was infected with virus spreading northward from Cape Town, not from the much closer Atlantic coast. From Boston, the fall wave spread across the United States in six weeks. In Philadelphia, 10,959 people died of influenza in October. Military outposts were again hot spots. Between Sept. 12 and Oct. 11, 37 Army installations suffered outbreaks. Stanley S. Lane, who'd given a false birth date on his enlistment papers, was five days shy of his 17th birthday when influenza struck Camp McClellan in Alabama on Sept. 26. "All I remember about it was I got a little temperature and I went on sick call and the doctor said, 'Go to the hospital, you got the flu,' " he recalled recently at his home in Silver Spring. "When I walked in there the nurse says, 'That's your bed over there.' So I went over and sat down. And the greetings I got was from all these other GIs around there telling me: 'Hey, the guy who just left that bed died,' " Lane, now 101, said with a slight chuckle. "It didn't bother me. I went to bed." He doesn't recall his illness as being especially severe. In any case, he recovered and went on to spend 32 years in the Army, retiring as a lieutenant colonel. The Spanish flu had an unusual and unexplained predilection for young adults, whom it killed in greater numbers than either children or the elderly. Many of Lane's fellow soldiers weren't as lucky as he. About 20,000 died in nine weeks in the United States that fall. Troops in Europe were rapidly infected as well. The American Expeditionary Forces recorded 37,000 cases of influenza in September -- and 16,000 more in the first week of October. No army was immune. "Influenza gummed up the German supply lines and made it harder to advance and harder to retreat," historian Crosby wrote. "It made running impossible, walking difficult, and simply lying in the mud and breathing burdensome. From the point of view of the generals, it had a worse effect on the fighting qualities of an army than death itself." Russia, out of the war, was finally breached on Sept. 4, when American troops on two ships arrived in Archangel on the White Sea to support a British campaign against the Bolsheviks. It then moved south and east, decimating a civilian population crowded indoors for the winter and weakened by the chaos of the revolution and an ongoing epidemic of typhus. As in the current SARS epidemic, outbreaks of Spanish influenza could sometimes be traced to a single person. In some cases, there were people who barely became ill but who nevertheless transmitted the virus to many people who were soon killed by it. An analysis of the British Navy's experience, reported in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1921, provides a dramatic example. A transport carrying 1,150 troops from New Zealand anchored off Freetown. Influenza was raging on shore and on some British warships nearby. Unwisely, a conference of ship captains was called on one of them. "The captain of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force transport sat next to the captain of the warship. The former did not suffer from influenza subsequently, although he felt rather 'off colour' for the few days following. There had been absolutely no contact between shore and transport, although some provisions were apparently delivered to the ship's side. Influenza [began] when the ship was about four days out and increased quickly in violence until practically all of the soldiers were more or less affected," according to the account. In all, there were 900 serious cases and 83 deaths. Around the world, wide and cruel variations in mortality were the rule. Poor and marginally nourished people, not surprisingly, fared worst. India lost about 18.5 million people, just less than 6 percent of its population. In the United States, 675,000 people died, about 0.7 percent of the population. In northern Nigeria, mortality among the general population of Europeans was 19 per 1,000; among Nigerians, it was 32 per 1,000. Some aboriginal populations were decimated. Mortality in Alaska was horrifying. In one settlement, Brevig Mission, 72 out of 80 natives died in five days, leaving only children and teenagers. As with SARS today, quarantine was the main tool against Spanish influenza. There were no effective medicines. In fact, it wasn't even known that a virus caused the disease. The influenza virus wasn't isolated until 1933, and in 1918 most medical authorities attributed infection to Pfeiffer's bacillus, a bacterium found in the lungs of many serious cases that is known today as Haemophilus influenzae. Even in many places untouched by public health intervention, the value of quarantine was recognized instinctively. Warren T. Vaughan, a professor at Harvard Medical School, cites an example in a narrative history of the pandemic published in 1921. He quotes an account of a visitor to Lapland who described seeing settlements in which a typical one-room dwelling had been set aside for influenza patients, who had to stay there until they died or recovered. "Whilst there they received practically no attention, and no healthy person ever entered to attend to their wants. Occasionally a bowl of water or reindeer milk was hastily passed in at the door, or a huge chunk of reindeer meat thrown in, uncooked and uncarved," the visitor wrote. "The stench on opening the door met one like a poison blast and the rooms were nearly always ill lighted and dark. The patients lay littered about the floor in a crowded mass, fully dressed in clothes and boots . . . some, when we entered, sat up and with flushed faces and dull, uncomprehending eyes watched us listlessly." In general, though, quarantine worked poorly as it took just one infected person breaking isolation to spread disease. But in one place it worked famously, creating a classic "natural experiment" of epidemiology. The Samoan Islands in the Pacific Ocean were split between the United States, which controlled the eastern islands, and New Zealand, which had seized the western islands from Germany at the start of the world war. On Nov. 7, 1918, the steamship Talune, from New Zealand, anchored at Apia, the capital of Western Samoa. It carried people ill with flu. "Before the end of that year, a matter of less than two months, 7,542 died of influenza and its complications in Western Samoa, approximately 20 percent of the total population," Crosby writes. Without orders from the government but based on what he learned from a radio news service, the governor of American Samoa, Navy Cmdr. John M. Poyer, instituted a quarantine policy. When he heard of the outbreak on Western Samoa, he banned travel to or from the neighboring islands, which were about 40 miles apart. When the governor of Western Samoa, Lt. Col. Robert Logan, sent a boat with mail to American Samoa to be put on the itinerant mail boat docked there, Poyer refused even to allow the bags to be transferred. Enraged, Logan temporarily stopped all radio communication with the American islands. Poyer persuaded the island's natives to mount a shore patrol to prevent illegal landings. People who disembarked from ships sailing from the American mainland were kept under house arrest for a specified period, or examined daily. Aspects of the quarantine continued into mid-1920, a year after Poyer departed to the sound of a 17-gun salute. There were no influenza deaths on American Samoa. A third wave of Spanish influenza began in January 1919, circulating intensively for two months. Although that wave, too, caused many deaths, the virus was running out of victims. The winter of 1920 again saw flu with relatively high death rates. But people who'd been infected in 1918 and had survived were not protected during that outbreak, so it was probably caused by an entirely new strain of virus. Surprisingly, new and important things are being learned about the epidemic 85 years on. The death toll has been revised upward twice in the last 15 years. The estimate of global mortality of 21.5 million made in 1927 was superseded in 1991 by an estimate of 30 million, made by Patterson and Pyle. Last year two other historians, Niall P.A.S. Johnson and Juergen Mueller, calculated a global total again, using new material on mortality from Asian countries and African colonies that had been presented at a conference in South Africa in 1998. "Global mortality from the influenza pandemic appears to have been of the order of 50 million. However, even this vast figure may be substantially lower than the real toll, perhaps as much as 100 percent understated," they wrote. After-the-fact surveys of bloodstream antibodies suggests that 98 percent of Americans alive in 1918 and 1919 had been infected. At some point, on a day as lost to history as the one of its emergence, Spanish influenza made a final human being ill and then disappeared.

|

----------

----------