|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. BUSINESSWEEK Hispanic Nation Hispanics are an immigrant group like no other. Their huge numbers are challenging old assumptions about assimilation. Is America ready? By Brian Grow, with Ronald Grover, Arlene Weintraub, and Christopher Palmeri in Los Angeles, Mara Der Hovanesian in New York, Michael Eidam in Atlanta, and bureau reports June 14, 2004

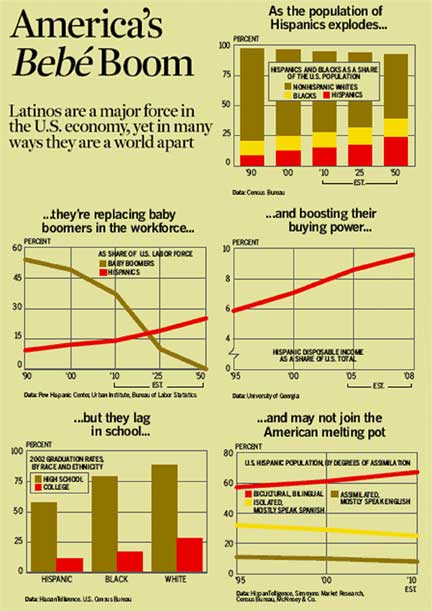

The Velazquezes speak fluent English and cherish their middle-class foothold in America. Maria and Carlos each earn about $20,000 a year as a school administrator and a graveyard foreman, respectively, and they own a simple three-bedroom home. But they remain wedded to their native language and culture. Spanish is the language at home, even for their five boys, ages 6 to 18. The kids speak to each other and their friends in English flecked with "dude" and "man," but in Cicero, where 77% of the 86,000 residents are Hispanic, Spanish dominates. The older boys snack at local taquerías when they don't eat at home, where Maria's cooking runs to dishes like chicken mole and enchiladas. The family reads and watches TV in Spanish and English. The eldest, Jesse, is a freshman at nearby Morton College and dreams of becoming a state trooper; his girlfriend is also Mexican-American. "It's important that they know where they're from, that they're connected to their roots," says Maria, who bounced between Spanish and English while speaking to BusinessWeek. She tries to take the kids to visit her parents in the tiny Mexican town of Valle de Guadalupe at least once a year. "It gives them a good base to start from." The Velazquezes, with their mixed cultural loyalties, are at the center of America's new demographic bulge. Baby boomers, move over -- the bebé boomers are coming. They are 39 million strong, including some 8 million illegal immigrants -- bilingual, bicultural, mostly younger Hispanics who will drive growth in the U.S. population and workforce as far out as statisticians can project (charts). Coming from across Latin America, but predominantly Mexico, and with high birth rates, these immigrants are creating what experts are calling a "tamale in the snake," a huge cohort of kindergarten to thirtysomething Hispanics created by the sheer velocity of their population growth -- 3% a year, vs. 0.8% for everyone else. It's not just that Latinos, as many prefer to be called, officially passed African Americans last year to become the nation's largest minority. Their numbers are so great that, like the postwar baby boomers before them, the Latino Generation is becoming a driving force in the economy, politics, and culture. Cultural Clout It amounts to no less than a shift in the nation's center of gravity. Hispanics made up half of all new workers in the past decade, a trend that will lift them from roughly 12% of the workforce today to nearly 25% two generations from now. Despite low family incomes, which at $33,000 a year lag the national average of $42,000, Hispanics' soaring buying power increasingly influences the food Americans eat, the clothes they buy, and the cars they drive. Companies are scrambling to revamp products and marketing to reach the fastest-growing consumer group. Latino flavors are seeping into mainstream culture, too. With Hispanic youth a majority of the under-18 set, or close to it, in cities such as Los Angeles, Miami, and San Antonio, what's hip there is spreading into suburbia, much the way rap exploded out of black neighborhoods in the late 1980s. Hispanic political clout is growing, too. In a Presidential race that's likely to be as tight as the last one, they could be a must-win swing bloc. Indeed, the increase in voting-age Hispanics since 2000 now outstrips the margin of victory in seven states for either President George W. Bush or former Vice-President Albert Gore, according to a new study by HispanTelligence, a Santa Barbara (Calif.) research group. Bush opened the election year with a guest-worker proposal for immigrants that pundits took as a play for the Latino vote. He will follow up by rekindling his relationship with Mexican President Vicente Fox, who's due to visit Bush at his Crawford, Texas, ranch on Mar. 5. Democrats, traditionally the dominant party among Hispanics, are stepping up their outreach, too. New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson, a Mexican-American and potential Vice-Presidential candidate, delivered a first-ever Spanish-language version of the Democrat's rebuttal to the State of the Union address. The U.S. has never faced demographic change quite like this before. Certainly, the Latino boom brings a welcome charge to the economy at a time when others' population growth has slowed to a crawl. Without a steady supply of new workers and consumers, a graying U.S. might see a long-term slowdown along the lines of aging Japan, says former Housing and Urban Development chief Henry Cisneros, who now builds homes in Hispanic-rich markets such as San Antonio. "Here we have this younger, hard-working Latino population whose best working years are still ahead," he says. Already, Latinos are a key catalyst of economic growth. Their disposable income has jumped 29% since 2001, to $652 billion last year, double the pace of the rest of the population, according to the Selig Center for Economic Growth at the University of Georgia. Similarly, the ranks of Latino entrepreneurs has jumped by 30% since 1998, calculates the Internal Revenue Service. "The impact of Hispanics is huge, especially since they're the fastest-growing demographic," says Merrill Lynch & Co. (MER ) Vice-President Carlos Vaquero, himself a Mexican immigrant based in Houston. Vaquero oversees part of the company's 350-person Hispanic unit, which is hiring 100 mostly bilingual financial advisers this year and which generated $1 billion worth of new business nationwide last year, double its goal. Yet the rise of a minority group this distinct requires major adjustments, as well. Already, Hispanics are spurring U.S. institutions to accommodate a second linguistic group. The Labor Dept. and Social Security Administration are hiring more Spanish-language administrators to cope with the surge in Spanish speakers in the workforce. Politicians, too, increasingly reach out to Hispanics in their own language. What's not yet clear is whether Hispanic social cohesion will be so strong as to actually challenge the idea of the American melting pot. At the extreme, ardent assimilationists worry that the spread of Spanish eventually could prompt Congress to recognize it as an official second language, much as French is in Canada today. Some even predict a Quebec-style Latino dominance in states such as Texas and California that will encourage separatism, a view expressed in a recent book called Mexifornia: A State of Becoming by Victor Davis Hanson, a history professor at California State University at Fresno. These views have recently been echoed by Harvard University political scientist Samuel P. Huntington in a forthcoming book, Who Are We. These critics argue that legions of poorly educated non-English speakers undermine the U.S. economy. Although the steady influx of low-skilled workers helps keep America's gardens tended and floors cleaned, those workers also exert downward pressure on wages across the lower end of the pay structure. Already, this is causing friction with African Americans, who see their jobs and pay being hit. "How are we going to compete in a global market when 50% of our fastest-growing group doesn't graduate from high school?" demands former Colorado Governor Richard D. Lamm, who now co-directs a public policy center at the University of Denver. Still, many experts think it's more likely that the U.S. will find a new model, more salad bowl than melting pot, that accommodates a Latino subgroup without major upheaval. "America has to learn to live with diversity -- the change in population, in [Spanish-language] media, in immigration," says Andrew Erlich, the founder of Erlich Transcultural Consultants Inc. in North Hollywood, Calif. Hispanics aren't so much assimilating as acculturating -- acquiring a new culture while retaining their original one -- says Felipe Korzenny, a professor of Hispanic marketing at Florida State University. It boils down to this: How much will Hispanics change America, and how much will America change them? Throughout the country's history, successive waves of immigrants eventually surrendered their native languages and cultures and melted into the middle class. It didn't always happen right away. During the great European migrations of the 1800s, Germans settled in an area stretching from Pennsylvania to Minnesota. They had their own schools, newspapers, and businesses, and spoke German, says Demetrios G. Papademetriou, co-founder of the Migration Policy Institute in Washington. But in a few generations, their kids spoke only English and embraced American aspirations and habits. Hispanics may be different, and not just because many are nonwhites. True, Maria Velazquez worries that her boys may lose their Spanish and urges them to speak it more. Even so, Hispanics today may have more choice than other immigrant groups to remain within their culture. With national TV networks such as Univision Communications Inc. (UVN ) and hundreds of mostly Spanish-speaking enclaves like Cicero, Hispanics may find it practical to remain bilingual. Today, 78% of U.S. Latinos speak Spanish, even if they also know English, according to the Census Bureau. Back and Forth The 21 million Mexicans among them also have something else no other immigrant group has had: They're a car ride away from their home country. Many routinely journey back and forth, allowing them to maintain ties that Europeans never could. The dual identities are reinforced by the constant influx of new Latino immigrants -- roughly 400,000 a year, the highest flow in U.S. history. The steady stream of newcomers will likely keep the foreign-born, who typically speak mostly or only Spanish, at one-third of the U.S. Hispanic population for several decades. Their presence means that "Spanish is constantly refreshed, which is one of the key contrasts with what people think of as the melting pot," says Roberto Suro, director of the Pew Hispanic Center, a Latino research group in Washington. A slow pace of assimilation is likely to hurt Hispanics themselves the most, especially poor immigrants who show up with no English and few skills. Latinos have long lagged in U.S. schools, in part because many families remain cloistered in Spanish-speaking neighborhoods. Their strong work ethic can compound the problem by propelling many young Latinos into the workforce before they finish high school. So while the Hispanic high-school-graduation rate has climbed 12 percentage points since 1980, to 57%, that's still woefully short of the 88% for non-Hispanic whites and 80% for African Americans. Meld into the Mainstream

Certainly immigrants often head for a place where they can get support from fellow citizens, or even former neighbors. Some 90% of immigrants from Tonatico, a small town 100 miles south of Mexico City, head for Waukegan, Ill., joining 5,000 Tonaticans already there. In Miami, of course, Cubans dominate. "Miami has Hispanic banks, Hispanic law firms, Hispanic hospitals, so you can more or less conduct your entire life in Spanish here," says Leopoldo E. Guzman, 57. He came to the U.S. from Cuba at 15 and turned a Columbia University degree into a job at Lazard Frères & Co. before founding investment bank Guzman & Co. Or take the Velazquezes' home of Cicero, a gritty factory town that once claimed fame as Al Capone's headquarters. Originally populated mostly by Czechs, Poles, and Slovaks, the Chicago suburb started decaying in the 1970s as factories closed and residents fled in search of jobs. Then a wave of young Mexican immigrants drove the population to its current Hispanic dominance, up from 1% in 1970. Today, the town president, equivalent to a mayor, is a Mexican immigrant, Ramiro Gonzalez, and Hispanics have replaced whites in the surviving factories and local schools. It's still possible that Cicero's Latino children will follow the path of so many other immigrants and move out into non-Hispanic neighborhoods. If they do, they, or at least their children, will likely all but abandon Spanish, gradually marry non-Hispanics, and meld into the mainstream. But many researchers and academics say that's not likely for many Hispanics. In fact, a study of assimilation and other factors shows that while the number of Hispanics who prefer to speak mostly Spanish has dipped in recent years as the children of immigrants grow up with English, there has been no increase in those who prefer only English. Instead, the HispanTelligence study found that the group speaking both languages has climbed six percentage points since 1995, to 63%, and is likely to jump to 67% by 2010. The trend to acculturate rather than assimilate is even more stark among Latino youth. Today, 97% of Mexican kids whose parents are immigrants and 76% of other Hispanic immigrant children know Spanish, even as nearly 90% also speak English very well, according to a decade-long study by University of California at Irvine sociologist Rubén G. Rumbaut. More striking, those Latino kids keep their native language at four times the rate of Filipino, Vietnamese, or Chinese children of immigrants. "Before, immigrants tried to become Americans as soon as possible," says Sergio Bendixen, founder of Bendixen & Associates, a polling firm in Coral Gables, Fla., that specializes in Hispanics. "Now, it's the opposite." Selling in Spanish

Other companies are making similar assumptions. In 2002, Cypress (Calif.)-based PacifiCare Health Systems Inc. (PHS ) hired Russell A. Bennett, a longtime Mexico City resident, to help target Hispanics. He soon found that they were already 20% of PacifiCare's 3 million policyholders. So Bennett's new unit, Latino Health Solutions, began marketing health insurance in Spanish, directing Hispanics to Spanish-speaking doctors, and translating documents into Spanish for Hispanic workers. "We knew we had to remake the entire company, linguistically and culturally, to deal with this market," says Bennett. A few companies are even going all-Spanish. After local Hispanic merchants stole much of its business in a Houston neighborhood that became 85% Latino, Kroger Co. (KR ), the nation's No.1 grocery chain, spent $1.8 million last year to convert the 59,000-sq.-ft. store into an all-Hispanic supermercado. Now, Spanish-language signs welcome customers, and catfish and banana leaves line the aisles. Across the country, Kroger has expanded its private-label Buena Comida line from the standard rice and beans to 105 different items. As the ranks of Spanish speakers swell, Spanish-language media are transforming from a niche market into a stand-alone industry. Ad revenues on Spanish-language TV should climb by 16% this year, more than other media segments, according to TNS Media Intelligence/CMR. The audience of Univision, the No.1 Spanish-language media conglomerate in the U.S., has soared by 44% since 2001, and by 146% in the 18- to 34-year-old group. Many viewers have come from English-language networks, whose audiences have declined in that period. In fact, Univision tried to reach out to assimilated Hispanics a few years ago by putting English-language programs on its cable channel Galavision. They bombed, says Univision President Ray Rodriguez, so he switched back to Spanish-only in 2002 -- and 18- to 34-year-old viewership shot up by 95% that year. "We do what the networks don't, and that's devote a lot of our show to what interests the Latino community," says Univision news anchor Jorge Ramos. The Hispanicizing of America raises a number of political flash points. Over the years, periodic backlashes have erupted in areas with fast-growing Latino populations, notably former California Governor Pete Wilson's 1994 effort, known as Proposition 187, to ban social services to undocumented immigrants. English-only laws, which limit or prohibit schools and government agencies from using Spanish, have passed in some 18 states. Most of these efforts have been ineffective, but they're likely to continue as the Latino presence increases. For more than 200 years, the nation has succeeded in weaving the foreign-born into the fabric of U.S. society, incorporating strands of new cultures along the way. With their huge numbers, Hispanics are adding all kinds of new influences. Cinco de Mayo has joined St. Patrick's Day as a public celebration in some neighborhoods, and burritos are everyday fare. More and more, Americans hablan Español. Will Hispanics be absorbed just as other waves of immigrants were? It's possible, but more likely they will continue to straddle two worlds, figuring out ways to remain Hispanic even as they become Americans.

|

Maria Velazquez was born in a dingy hospital on the U.S.-Mexican border and has been straddling the two nations ever since. The 36-year-old daughter of a bracero, a Mexican migrant who tended California strawberry and lettuce fields in the 1960s, she spent her first nine years like a nomad, crossing the border with her family each summer to follow her father to work. Then her parents and their six children settled down in a Chicago barrio, where Maria learned English in the local public school and met Carlos Velazquez, who had immigrated from Mexico as a teenager. The two married in 1984, when Maria was 17, and relocated to nearby Cicero, Ill. Her parents returned to their homeland the next year with five younger kids.

Maria Velazquez was born in a dingy hospital on the U.S.-Mexican border and has been straddling the two nations ever since. The 36-year-old daughter of a bracero, a Mexican migrant who tended California strawberry and lettuce fields in the 1960s, she spent her first nine years like a nomad, crossing the border with her family each summer to follow her father to work. Then her parents and their six children settled down in a Chicago barrio, where Maria learned English in the local public school and met Carlos Velazquez, who had immigrated from Mexico as a teenager. The two married in 1984, when Maria was 17, and relocated to nearby Cicero, Ill. Her parents returned to their homeland the next year with five younger kids.

The failure to develop skills leaves many Hispanics trapped in low-wage service jobs that offer few avenues for advancement. Incomes may not catch up anytime soon, either, certainly not for the millions of undocumented Hispanics. Most of these, from Mexican street-corner day laborers in Los Angeles to Guatemalan poultry-plant workers in North Carolina, toil in the underbelly of the U.S. economy. Many low-wage Hispanics would fare better economically if they moved out of the barrios and assimilated into U.S. society. Most probably face less racism than African Americans, since Latinos are a diverse ethnic and linguistic group comprising every nationality from Argentinians, who have a strong European heritage, to Dominicans, with their large black population. Even so, the pull of a common language may keep many in a country apart.

The failure to develop skills leaves many Hispanics trapped in low-wage service jobs that offer few avenues for advancement. Incomes may not catch up anytime soon, either, certainly not for the millions of undocumented Hispanics. Most of these, from Mexican street-corner day laborers in Los Angeles to Guatemalan poultry-plant workers in North Carolina, toil in the underbelly of the U.S. economy. Many low-wage Hispanics would fare better economically if they moved out of the barrios and assimilated into U.S. society. Most probably face less racism than African Americans, since Latinos are a diverse ethnic and linguistic group comprising every nationality from Argentinians, who have a strong European heritage, to Dominicans, with their large black population. Even so, the pull of a common language may keep many in a country apart. In its eagerness to tap the exploding Hispanic market, Corporate America itself is helping to reinforce Hispanics' bicultural preferences. Last year, Procter & Gamble Co. (PG ) spent $90 million on advertising directed at Latinos for 12 products such as Crest and Tide -- 10% of its ad budget for those brands and a 28% hike in just a year. Sure, P&G has been marketing to Hispanics for decades, but spending took off after 2000, when the company set up a 65-person bilingual team to target Hispanics. Now, P&G tailors everything from detergent to toothpaste to Latino tastes. Last year, it added a third scent to Gain detergent called "white-water fresh" after finding that 57% of Hispanics like to smell their purchases. Now, Gain's sales growth is double-digit in the Hispanic market, outpacing general U.S. sales. "Hispanics are a cornerstone of our growth in North America," says Graciela Eleta, vice-president of P&G's multicultural team in Puerto Rico.

In its eagerness to tap the exploding Hispanic market, Corporate America itself is helping to reinforce Hispanics' bicultural preferences. Last year, Procter & Gamble Co. (PG ) spent $90 million on advertising directed at Latinos for 12 products such as Crest and Tide -- 10% of its ad budget for those brands and a 28% hike in just a year. Sure, P&G has been marketing to Hispanics for decades, but spending took off after 2000, when the company set up a 65-person bilingual team to target Hispanics. Now, P&G tailors everything from detergent to toothpaste to Latino tastes. Last year, it added a third scent to Gain detergent called "white-water fresh" after finding that 57% of Hispanics like to smell their purchases. Now, Gain's sales growth is double-digit in the Hispanic market, outpacing general U.S. sales. "Hispanics are a cornerstone of our growth in North America," says Graciela Eleta, vice-president of P&G's multicultural team in Puerto Rico.