|

|

Para ver este documento

en español, oprima aquí.

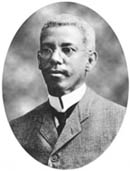

Puerto Rico Profile: José Celso Barbosa

December 3, 1999

Copyright © 1999 THE PUERTO RICO HERALD. All Rights Reserved.

José Celso

Barbosa is one of the giants of Puerto Rican history, a man who

aspired tirelessly for the success of himself and his people.

A Puerto Rican of African descent, Barbosa had to overcome racism

and discrimination throughout his life. He lived for 64 years,

from 1857 to 1921, during which the people of Puerto Rico waged

an ongoing struggle for social and political freedom. He was born

in Bayamón, the son of a bricklayer in what was then a

corner of the Spanish Empire. He died an influential physician,

a great Puerto Rican, an American citizen, and one of the most

important black men of his time. José Celso

Barbosa is one of the giants of Puerto Rican history, a man who

aspired tirelessly for the success of himself and his people.

A Puerto Rican of African descent, Barbosa had to overcome racism

and discrimination throughout his life. He lived for 64 years,

from 1857 to 1921, during which the people of Puerto Rico waged

an ongoing struggle for social and political freedom. He was born

in Bayamón, the son of a bricklayer in what was then a

corner of the Spanish Empire. He died an influential physician,

a great Puerto Rican, an American citizen, and one of the most

important black men of his time.

100 years ago, on July 4, 1899, Barbosa was the founder of

the Republican Party of Puerto Rico. The moment marked the culmination

of Barbosa's vision for the future of Puerto Rico, a future in

which liberty and opportunity would be guaranteed through permanent

union with the United States. A century after that pivotal moment

in Barbosa's life, it is instructive to consider briefly the roots

of his belief in statehood for Puerto Rico.

All his life, Barbosa was an underdog. Like anyone who manages

to succeed against great odds, he had unrealistic and improbable

goals, and he turned them into realities. Time and again, he overcame

enormous obstacles through a combination of vision, talent, and

determination. As he found personal success, he used these same

attributes to work for the future of Puerto Rico.

The driving force of Barbosa's early years was his Aunt Lucía

Triano, or "Mamá Lucía." She recognized

the potential in the young "Pepito," and devoted herself

to his education. Thanks to her patronage and his considerable

talent, Barbosa was admitted in 1870 to the Seminario Consiliar

de San Juan, the only secondary school on the island. At this

Jesuit institution, Barbosa was ridiculed for being poor and black;

yet he excelled at the rigorous classical curriculum despite the

hostile environment.

For the next step in his education, Barbosa was sent on a sugar

boat to New York, where he learned English with the intention

of studying at Columbia University. When Columbia rejected him

because of his race, he turned instead to the University of Michigan,

where he studied medicine.

While at Michigan, Barbosa developed a deep and life-long affinity

for the American political system and its principles. He noted

that Thomas Jefferson had urged a nephew to learn Spanish because

of its role in the foundation of American civilization. He also

greatly admired Abraham Lincoln, emancipator of the slaves and

champion of the values that gave Barbosa his opportunity to excel.

In 1880, Barbosa received his degree in medicine from the University

of Michigan. He was the top student in his class.

When he returned to Puerto Rico later that year, Barbosa once

again met with resistance, this time while trying to establish

a medical practice. Once again, however, his skill and determination

broke through the barrier of race, and he became a prominent physician.

Toward the end of the 1880s, Barbosa entered politics as a

member of the secret societies aiming to undermine the Spanish

colonial presence. As he later recounted, the purpose of these

societies which nurtured a generation of Puerto Rican leaders

was to work for "the assistance, the protection, and

the mutual defense between the Puerto Ricans for their material

and moral progress, in order to safeguard their precarious economic

situation, and so that they could once again be owners, even of

a small portion, of the sources of wealth of their land."

A decade later, Barbosa came to believe that these goals could

be best attained through union with the United States. He saw

in the United States despite serious flaws in execution

a system and structure with the ability to establish and

insure freedom. Thus in 1898, speaking for a group of autonomists,

he wrote: "We aspire to be another State within the Union

in order to affirm the personality of the Puerto Rican people."

What he wanted was not assimilation but true power through the

rights attendant to statehood.

Barbosa was undoubtedly a man ahead of his time. He championed

education and health issues with as much emphasis as we discuss

these issues today. Moreover, he shattered the limited conceptions

of what it meant in the 19th Century to be black and to be Puerto

Rican; and in doing so, he became a great black man, a great Puerto

Rican, and a great American.

|